|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

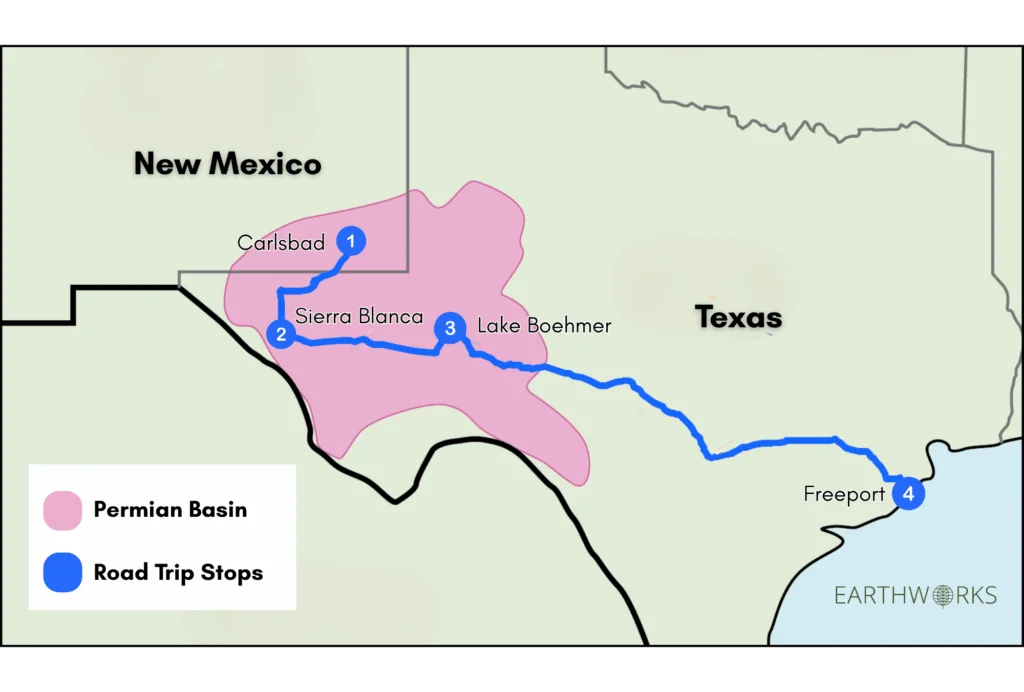

This summer, Earthworks embarked on a road trip with partners that started in the Permian Basin, which spans from West Texas to Southeastern New Mexico, and ended on the Texas Gulf Coast. Record-breaking production of oil and gas in the Permian Basin has made the U.S. the world’s top oil and gas exporter, causing environmental and health harms in communities all along the supply chain. This is the third blog in a series documenting those harms. Click here to read the first.

From Sierra Blanca, we journeyed east to more oilfields of the Permian Basin, where pumpjacks dot the sparse, desert landscape. The Permian Basin, which spans from Southeastern New Mexico to West Texas, produces nearly half of the United States’ crude oil and a quarter of the nation’s methane. The oil and gas industry brags about this, but this has left the region with tens of thousands of leaky, abandoned, toxic wells that impact the land, water, and communities.

Here, we met Hawk Dunlap, a lifelong oilfield worker and well control specialist who is unafraid to speak out about the destruction the industry has left behind. On the 22,000 acre Antina Ranch owned by Ashley Watt — roughly twice the size of Manhattan — Dunlap monitors the 330 wells on the ranch and has uncovered a troubling trend. Of the 150 wells that he has actively investigated, all have shown signs of leaking, despite supposedly being plugged by the company that owned them. The leaks are underground, potentially polluting the groundwater. When the emissions make it to the surface, they release harmful chemicals into the air as well. Because the operators have theoretically plugged these wells, no one except the state of Texas is left responsible for all of this pollution, and they make no effort to clean them up.

Dunlap spent the bulk of his career travelling the world, working on oilfield fires and explosions. What he sees in Texas’s Permian Basin, he says, is worse than anything he has seen elsewhere.

Corporate Negligence, Community Risk

Leaky wells are caused by a combination of underground pressure from wastewater being injected underground, and poor plugging practices. In 2022, Watt filed a lawsuit against Chevron and other companies she believes are responsible for the leaking wells on her ranch.

Large international oil companies like Chevron, Hawk tells us, “are not doing any root cause analysis. They’re refilling the cement, getting a rubber stamp by the Railroad Commission and driving off. But the plugs fail.”

The Railroad Commission is a misnomer for the Texas agency responsible for regulating oil and gas activities, not railroads. In the 1980s, smaller oil companies went out of business and larger corporations, like Chevron, bought them up. Hawk points to this shift as when orphaned- and zombie wells started to pop up.

“Across the state, we now have injection of produced water, poor plugging practices, histories of water flooding, the list goes on,” Dunlap says.

To inspect and clean up a mess of this scale would be extremely expensive. Yet, fossil fuel companies continue to take in record-breaking profits, and Texas’s regulatory agencies enact few regulations and little enforcement of their operations.

Wastewater: an industry problem with no real solution

Hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking”, involves blasting water and chemicals underground to squeeze more oil from the rock. The Permian Basin produces 6.4 million barrels of crude oil every day and for every barrel of crude oil produced, 3 to 5 barrels of salinated, chemically contaminated wastewater is produced.

Rather than treating the contaminated wastewater, which is expensive, the oil and gas industry pumps it back underground, in injection wells, which put pressure on existing and old wells. And if those old wells have been plugged hastily or are abandoned by their owners, they can burst loose, contaminating the land and drinking water. Underground injection and leaking wells threaten freshwater aquifers, which are a crucial source of drinking water for millions of Texans.

Lake Boehmer: A Case Study in Failure

Not far from Antina Ranch lies an example of the costs of the fossil fuel industry’s negligence. A massive yet little-known environmental disaster called Lake Boehmer bubbles up from the desert, covering an area of 60 acres with toxic water. Only a small sign, lying broken on the side of the road, warns of the hazard, yet the wind reeks with hydrogen sulfide.

Originally drilled as an oil and gas exploration well, Lake Boehmer was later converted into a water well. Over the years, the steel casing that is supposed to keep the well contained corroded and contaminated water and co-mingled with artesian spring water. Now, an uncontrolled, artificial lake spews toxic, saline water across the desert. The well’s integrity is so compromised that any intervention could worsen the problem. State agencies like the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) and the Railroad Commission (RRC) have spent years pointing fingers at each other, instead of fixing the problem. Hawk suspects the land beneath the site is subsiding, making the disaster even more unstable.

Meanwhile, the oil and gas industry pushes risky schemes like carbon capture and storage (CCS), which requires injecting massive volumes of carbon dioxide (CO₂) underground. Carbon injection wells pose similar risks as wastewater injection, compromising the integrity of geological formations underground.

For Dunlap, the solution is clear: companies should pay to clean up their own mess, rather than spending public tax dollars plugging wells. In 2024, Hawk ran for Texas Railroad Commissioner, on a platform of corporate accountability. He’s running again in 2026 as a Republican. But until state and federal regulatory agencies hold corporate polluters accountable to address these problems, abandoned and zombie wells across the Permian Basin will continue to compromise land, water, and communities while corporations rake in profits.