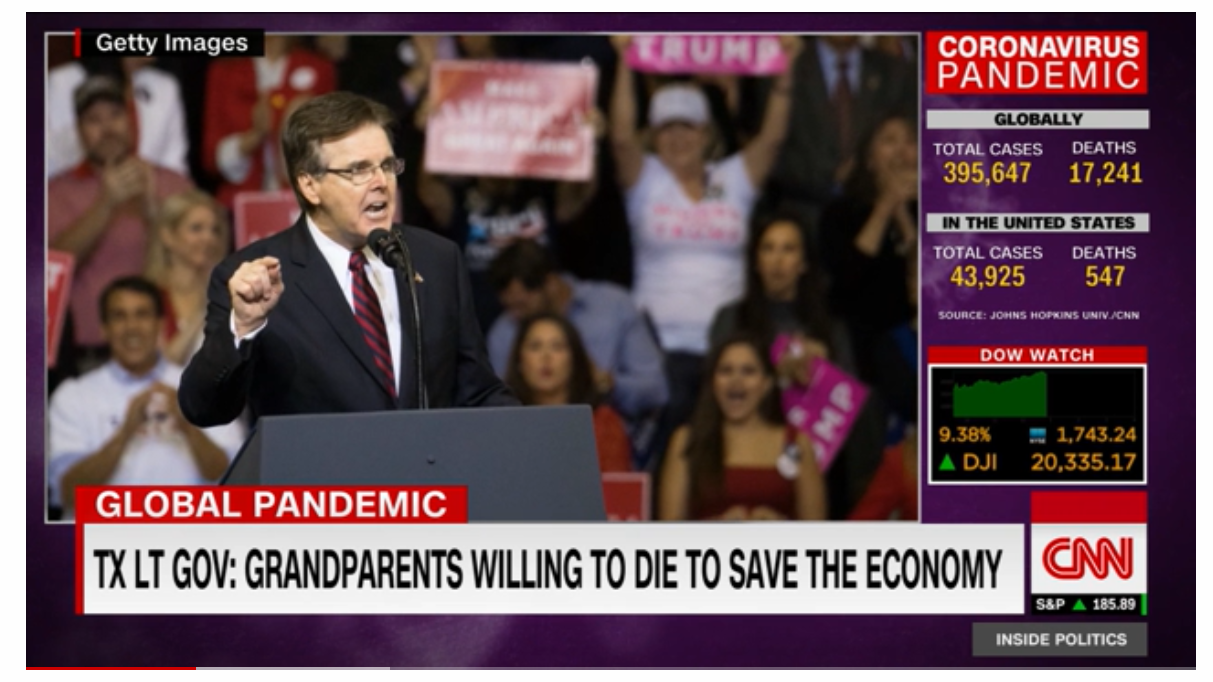

When Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick said “There are things more important than living“ about reopening businesses related to COVID-19, his comments quickly garnered national attention. Many people were shaken by the callous nature of the quote. However, Patrick was alluding to an often-taboo aspect of policy creation, the human cost of public policy. What made Patrick’s quote unique is that typically when talking about policy in this regard, politicians are not as forthcoming about the human collateral damage of their positions.

For many who live near oil and gas operations, Patrick’s jarring comment betrays a mindset that feels tragically familiar. It is common to hear about how the benefits of relying on fossil fuels outweigh the risks posed by an inherently polluting form of energy. The part typically not said out loud is that “the risks” include health risks to real people – those who work for the industry who can be exposed to hazards with little or no protection as well as people who live close to, downwind, and downstream of wells, pipelines, processing plants, refineries, and more. Human life is often just another variable in a cost/benefit analysis.

Texas lawmakers and oil and gas companies often tout the benefits of energy independence and free-market pursuit of a Texas-strong oil and gas industry. The implicit argument is that the people who become ill or die because of a polluter or a regulator’s actions (or lack thereof) are worth less than the upside benefits to the state and the nation. Energy independence is worth the rapid acceleration of climate change. Expanding a fossil fuel company’s profits is worth drilling next to a childcare center.

Hearing a leader in Patrick’s position so casually put a value on human life can be disturbing, but it is clarifying. As a society, we are constantly evaluating the value of a human life when we make decisions on policies from the speed limit to acceptable side effects of medication. Many who live in the oil and gas “sacrifice zone” wonder how companies value a human life when they decide where to drill? How does the Texas Senate (of which Dan Patrick is the President) value a human life when they allocate money to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and the Texas Railroad Commission (the state agencies that oversee the oil and gas industry) for regulation, monitoring, and enforcement?

According to Dr. Steven Hamburg, co-author of the newest study from the Environmental Defense Fund, Harvard University, Georgia Tech and the SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, the Permian Basin has “the highest emissions ever measured from a major U.S. oil and gas basin. There’s so much methane escaping from Permian oil and gas operations that it nearly triples the 20-year climate impact of burning the gas they’re producing.” When we couple that with our knowledge that methane leaks, as well as fracking in general, pose both an acute risk to human health as well as a broader climate level impact, it seems evident that the value lawmakers and the oil and gas industry put on a human life falls far short of what that person’s mother, brother or friend would say is equitable.

A recent unsettling example of this calculation happened just this month; The Trump Environmental Protection Agency gutted rules enacted during the Obama administration to help reduce methane and associated pollution from oil and gas operations and thereby mitigate the danger to humans and the acceleration of climate change. What changed? There was no data exonerating methane and volatile organic compounds from causing harm. Was it simply that the Trump administration’s Environmental Protection Agency devalued life in the equation that suddenly made an important environmental regulation not so important anymore?

So what needs to change? The simple answer is a lot, but we can start with changing the way we understand and evaluate the responsibility of the oil and gas industry to prevent, control, and clean up their own pollution. In the status quo, the presumption is that oil and gas companies are not polluting unless a member of the public or regulator proves otherwise.

People living near drilling must depend on researchers or a non-profit like Earthworks to bring in expensive optical gas imaging (OGI) or air sampling equipment to record pollution and hope the TCEQ investigates their complaint despite limited resources and a persistent lack of political will. The burden of proof is on those who are impacted by, not those who are profiting from, an action–when the precautionary principle makes clear it should be the other way around. In the case of oil and gas impacts, once a complaint is presented the presumption of harm should shift in the other direction, toward industry. If the industry faced fines or shut-downs until they proved they were operating safely, all parties’ interests would be aligned on getting leaks addressed quickly. If the value of human life is not enough, and let’s be clear it should be, maybe aligning it with an impact to operations is the work-around that forces policymakers and regulators to view the millions of people who live near oil and gas operations a little less expendable.