|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Today, Earthworks published Minimizing Mining Impacts on the Road to Zero Emissions Transport, the result of research commissioned through the Institute for Sustainable Futures at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) to study short-term strategies to meaningfully reduce mineral demand for the energy transition. The report offers policymakers and other decision-makers in all levels of governance examples of policies that reduce dependence on personal vehicles, while improving public health outcomes and significantly lowering the need for primary mineral extraction.

These policies are important for people living in cities–fewer cars means reduced emissions, sprawl, and pedestrian fatalities–as well as for the future of the planet, since minerals and metals mining and processing “account for 17 per cent GHG emissions and almost a quarter (24 percent) of global pollution” according to the UN Environment Program. The technologies and policy pathways for reducing mineral demand are there, and if policy makers begin to prioritize them, they will have immediate, tangible benefits.

This report echoes many of the key findings from previous UTS research, including the importance of recycling energy transition minerals (ETMs) and the potential benefits of wide-reaching demand reduction strategies. These three reports all conclude that ETM demand projections are neither set in stone nor inflexible. They emphasize that achieving a just transition, including for communities on the front lines of ETM extraction, processing, and waste management, requires rethinking energy consumption, especially for those of us in the Global North. As Minimizing Mining Impacts demonstrates, this rethinking is happening all over the world through all levels of government: from aggressively expanding public transit to partnering with micro-mobility companies, creative solutions for reducing mineral demand are bettering the lives of millions of people.

Any conversation about decarbonization in countries like the United States necessitates a conversation about transportation: according to the EPA, light-duty vehicles (LDVs), or passenger vehicles, are the country’s largest source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Governments and the auto and mining industries advocate for replacing every internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle with an electric vehicle (EV) as the most important and impactful climate action.

However, EV batteries require minerals, such as cobalt, nickel, and lithium, among others, the extraction of which often pollutes land, water, and air. Replacing every ICE vehicle with an EV risks further endangering Indigenous and other frontline communities worldwide with increased mining without adequate protections. These same communities are some of the most vulnerable to the climate crisis and, in Indigenous Peoples’ case, are also the protectors of 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity, which is crucial for preventing the climate crisis from worsening even further and remaining within planetary boundaries.

Fortunately, it is both possible and necessary for the countries that consume the most energy to reduce their demand for ETMs as they transition their economies away from fossil fuels. Or, as Minimizing Mining Impacts explains, “It is essential that solutions for decarbonization minimize the amount of mining required, and when mining is required, it must be done as responsibly as possible.”

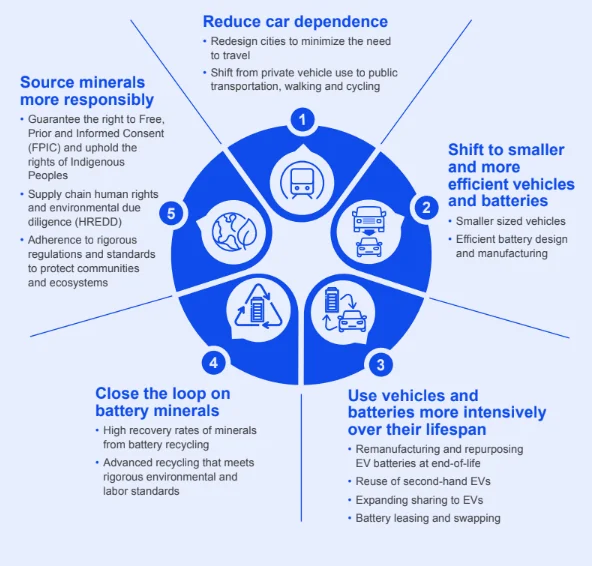

The report articulates five principles for minimizing mineral demand and the mining impacts of EVs:

- Reduce car dependence, including redesigning cities to encourage a shift from private vehicle use to public transportation, walking, and cycling.

- Shift to smaller and more efficient vehicles and EV batteries, including more efficient vehicle design and manufacturing.

- Use vehicles and batteries more intensively over their lifespan.

- Close the loop on battery materials with advanced recycling and recovery, such as by improving recovery rates and ensuring recycling meets rigorous environmental and labor standards.

- Source minerals responsibly by ensuring respect for Indigenous Peoples’ right to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), undertaking supply chain human rights and environmental due diligence (HREDD), and adhering to the most rigorous standards for mining operations.

While these big-picture ideas may be intimidating, they are proven and achievable. Cities and countries around the world have implemented many of these principles at various levels of governance for decades now, as the case studies in Minimizing Mining Impacts demonstrate. For example, Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, implemented an entirely new public transit system in 2000 after decades of increasingly worsened air quality and traffic congestion due to high private vehicle and low public transit use. The transit authority launched 41 kilometers (~25 miles) of bus routes, which has since expanded to more than 110 kilometers (~68 miles). According to Minimizing Mining Impacts, this “has resulted in reduced passenger travel time of 30%, a 92% reduction in road-related deaths, decreased car usage (9% of passengers previously commuted by private car), and a 40% reduction in air pollutants.” While there will always be room for improvement, the incredible progress the government of Bogotá has made in less than 30 years should interest leaders in cities with similar air pollution, congestion, and density situations.

Bogota’s public transit infrastructure shows one way cities can reduce car dependence. Gogoro, a Taiwanese company that produces electric scooters and runs the world’s largest battery swapping network for electric scooters, proves that there are viable alternatives to vehicle and battery ownership. They have 2,727 swap stations in nine countries for 47 scooter models. Not only are their products a much better alternative to cars (electric two-wheelers produce up to 67% lower GHG emissions per passenger [kilometer] and are up to 93 times faster to refuel compared to other low emission vehicles), but their model keeps both batteries and scooter parts in use for as long as possible, significantly reducing the need for primary mineral extraction.

Although the task of reducing mineral demand may seem overwhelming, it is not unprecedented. As Minimizing Mining Impacts explains, the solutions are already here, they’re accessible, and they’re mandatory for any actually just transition. All we need is the political will to make them a reality.