This blog was co-written with Raphael Breit, Earthworks’ Community Empowerment Project Coordinator.

The BLM will open its latest lease auction in December, putting about 200 acres on the market for oil and gas developers. As Earthworks enters this conversation, we began investigating the older oil and gas wells already occupying the forest. We uncovered serious pollution problems at these existing wells–a warning sign of what could happen with even more drilling and fracking.

Earthworks uses a highly specialized, industry-standard optical gas imaging (OGI) camera and quantification tools to detect, document, and measure leaks from oil and gas facilities, new and old. In March, we partnered with Ohio Environmental Council (OEC) and university researchers to inspect a series of the National Forest’s more than 1,200 active conventional wells. “Conventional” wells are generally shallower and lower-producing than “unconventional” wells; however, both may use hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) and can cause water and air pollution. Visitors to Wayne National Forest might stumble across such a well — some are in plain view of the road, others sit at the end of what seem to be hiking trails.

Most of the sites we visited lacked fencing or clear signage to warn passersby–although the National Forest’s website includes these words of warning:

“Keep away from oil/gas operations, they are private property and potentially dangerous. Pumpjacks may begin to operate without warning and any open flame, firearm discharge, or spark could cause an explosion.”

Polluted air on public land

While visiting the Wayne National Forest in March, our OGI camera picked up steady leaks at four sites, some of which we calculated to be emitting .62 lbs of pollution per hour. Using hand-held “sniffer” tools,our research partners determined that methane constituted some portion of all of these leaks. According to scientists from across the globe, methane is 86 times more powerful a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide on a 20-year timescale.

Besides methane, oil and gas wells are known to emit a host of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) into the air — for example, benzene, a known carcinogen — potentially exposing forest users to unexpected toxics. At several sites, we also documented oil spills, and one site showed evidence of wildlife drinking from salty, contaminated wastewater flowing up from around the well bore.

The Underground Railroad in the Wayne National Forest

Amid the leaking wells, in the Wayne, we also learned about another piece of the Forest’s unique history.

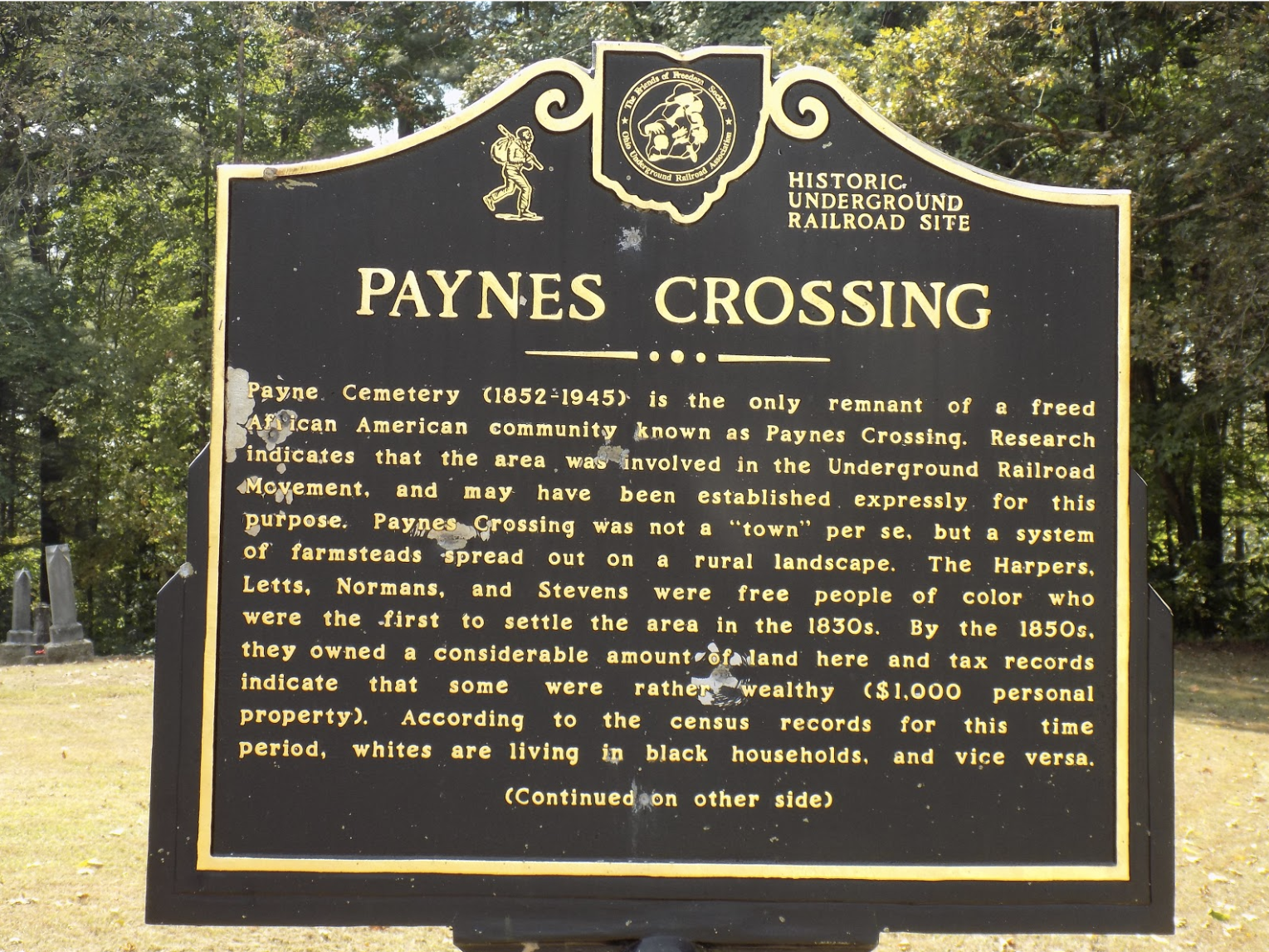

It wasn’t until looking at maps of the oil and gas wells in the WNF that I noticed — in the middle of the woods — that there was a town labeled just yards away from the area we were in. This seemed unlikely, given the dense plant growth and the remoteness of the location. The US Forest Service page revealed something even more intriguing: that the former town of Payne’s Crossing — was a vital waystation on the Underground Railroad.

Founded in the 1830’s, mostly by freed or runaway slaves from Virginia, Payne’s Crossing was a loose collection of farmsteads spread out across the rural landscape. The residents of Payne’s Crossing and other communities were labeled “free” to differentiate them from the enslaved living in southern geographies. By the Forest Service’s description of these historic communities, material goods were limited and survival was tenuous.Many of the town’s men enlisted in the U.S. Colored Troops to fight in the Civil War. However, others stayed behind, perhaps to continue Underground Railroad activities.

Unfortunately, near the end of the 19th century, coal companies purchased much of the land in the area, and by 1900, many families had moved away. Coal mining operations over the subsequent decades obscured most of the remains of the community.

The Payne Cemetery, which was used from 1852 to 1945, is the only remaining part of the town. Having long fallen into disrepair, the cemetery was recently restored through the efforts of many local partners, including the Lancaster Genealogical Society. The cemetery is now part of the national Passport in Time Program, through which genealogists have reunited families and helped piece together the town’s forgotten history.

In March and again in September, Earthworks certified thermographers documented leaks at the site featured above.

What remains of this historic location is a cemetery, and a wealth of archeological and historical data still to be uncovered, shared, and celebrated. According to the Forest Service,

“People want to know, discover and understand this very painful, yet inspirational piece of American History. It’s time it was told. And we, the Forest Service, have a part in that story. The ball is in our court, people expect us to run with it. We believe this is important, it’s part of our mission, and it’s the right thing to do.”

We couldn’t agree more strongly. Yet the polluting oil and gas wells seem to visibly contradict the Forest Service’s mission to preserve and honor this place and its former inhabitants.

Earthworks visited the Wayne again in September and confirmed that leaks and air pollution at all four sites continue, and we documented emissions at four additional sites. To date, we have not received a notification to the four complaints we filed with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) in March. It’s clear that current rules and the resources allotted to state and federal regulators fall woefully short of protecting the forest’s natural wonders and human history. This track record underscores just how reckless it would be to open these public lands to even more intensive, polluting and dangerous drilling.

More info:

- See more footage of normally invisible air pollution in the Wayne National Forest, and oil & gas development across Ohio, at bit.ly/CEP-OH

- Learn about the oil & gas industry’s waste and pollution in Pennsylvania public lands: https://earthworks.org/blog/part-of-the-public-land-experience-waste-and-pollution/