The Gulf of Ulloa off the coast of Baja California Sur, Mexico teems with marine life, from gray whales to lobster. Its seafloor is also rich in phosphate, a key component of fertilizers, at the center of a multi-billion-dollar arbitration suit that U.S. company Odyssey Marine Exploration has brought against Mexico under the terms of the original North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Odyssey, a treasure hunting firm turned mining company with little revenue of its own, secured financing from a private litigation firm in the US to file the claim after local opposition arose to its project and Mexican authorities denied it an environmental permit.

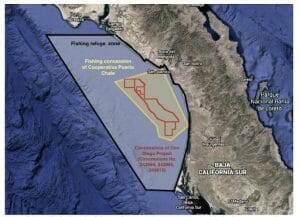

The fishing concessions of the Puerto Chale Fishing Cooperative are where the company would like to dredge the seafloor. The Cooperative has opposed the project from the start and filed for permission to submit its concerns to the NAFTA tribunal in October with help from the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL). They sought to communicate the impacts that this company’s project could have on their lives and environment, and why it was correct for Mexico’s environmental regulator to turn down a permit for the seabed mine according to the precautionary principle as found in national and international law.

As is common for an arbitration system designed to favor transnational corporations, the NAFTA tribunal recently refused to admit their submission. The majority on the three person panel of highly paid corporate lawyers says the cooperative’s input is basically not relevant. Surprisingly, however, one arbitrator expressed a dissenting opinion, arguing that not only should the cooperative be heard, but that failing to admit their concerns exposes the failings of the arbitration system with potentially far reaching impacts on environmental protection in Mexico.

This case is not unique. Mining companies are bringing ever more arbitration suits over controversial projects that have given rise to broad community opposition over serious risks they pose to nature and community wellbeing. Puerto Chale’s concerns and exclusion from this current arbitration is further evidence of the unviability, not only of seabed mining, but of the international arbitration system itself.

Hunting for Treasure through International Arbitration

In the early 2000s, Odyssey Marine Exploration made headlines for major discoveries of centuries-old sunken ships filled with silver and gold. A decade later, with the treasure hunting business dried up and company shares dipping as low as two dollars, Odyssey jumped on the seabed mining boat, seeking a more lucrative business option by capitalizing on the false idea that future mineral demands require us to mine the ocean floor.

In 2012, Odyssey acquired a majority holding in Oceanic Resources (ExO) and obtained a 50-year, renewable concession for the Don Diego marine phosphate project in the Gulf of Ulloa. Projected to cover 91 million hectares, the project would use large vessels to dredge the seabed, uprooting rock, sand, and organisms, which would be then transported onto the ship and separated to obtain the phosphate sand. The remainder of the dredged material would be discharged back into the sea becoming a source of pollution, sedimentation, and potential radiation, given the presence of radioactive elements such as uranium and thorium.

Mexican environmental authorities denied Odyssey the environmental permit necessary to operate, arguing that the project is not viable based on the project’s projected impact on endangered species, such as the loggerhead turtle. The authorities cited Odyssey’s proposal to use unproven technology, as well as its lack of experience in mining, technical expertise, or robust data on the viability of the deposit.

Odyssey has sued at every stage of the process. It brought legal claims against a local journalist and the president of the Puerto Chale fishing cooperative to try to silence them. The company later dropped both suits. It also twice challenged the environmental authority in a federal tribunal in Mexico against the permit denial. Now, Odyssey is suing Mexico for the incredible sum of US$2.36 billion dollars in future lost potential profits claiming the permit denial was politically motivated and violated its rights as an investor under NAFTA. Without significant income of its own, the company made a deal with Poplar Falls LLC to back the costly NAFTA claim.

Communities in Baja California Sur Fight Back

Many environmental and citizens groups began organizing to oppose the Don Diego project when they heard about its permit request. At the center of the peaceful resistance and the most directly affected is the Puerto Chale Fishing Cooperative made up of 128 families who have protected and maintained their concession off the coast of Baja California Sur since 1958.

Odyssey’s phosphate project overlaps with the Cooperatives fishing concession, located about 12 miles off the coast of Baja California Sur near the seaside towns of San Juanico and Las Barrancas. “We fear that Odyssey’s project would destroy the marine ecosystem and our high quality, sustainable harvest of shellfish and lobster, not to mention the harvest of other aquatic species by smaller cooperatives and women’s groups inside our concession,” said Cooperative President, Florencio Aguilar Liera. “In total, more than 8,000 tons of clams, squid, shrimp, snail, dogfish, crab, lobster, and oysters are harvested from the gulf each year.”

In its submission to the NAFTA tribunal, the Cooperative argued that an environmental approval for the project would risk the health of their fishing concession, and in turn the livelihoods of the families that make up the Cooperative, as well as the larger local economy. The threat, they add, goes beyond the financial implications given the central role fishing plays in the culture and social fabric of their communities. The Cooperative also highlights the threat of phosphate extraction to the delicate interconnectedness of the biodiversity of the Gulf of Ulloa, which in addition to highly productive fishing grounds, is home to breeding and reproduction grounds of marine mammals. It also supports numerous species with special protections or in danger of extinction, including the logger head and caguama turtles.

Tribunal Refuses Puerto Chale, Reveals Own Bias

In its decision over the amicus published earlier this month, the tribunal revealed its own bias as part of an arbitration system that has no obligation to consider the myriad of harms that transnational investments such as Odyssey’s have on people and the planet.

A panel majority, two of three, refused to admit the amicus. They argue with little detail that neither the Cooperative nor CIEL have a “significant interest” in the case. According to the company-appointed arbitrator and the panel chair, the Cooperative’s input is not relevant because the company is presumably seeking compensation, not restitution of the project. CIEL, according to the panel, has the same general interest “that any environmental organization might have” in the case. According to them, neither would help the tribunal address legal or factual issues arising over the permit denial. This, despite the Cooperative having been an active participant in public hearings and other submissions over the company’s permit and CIEL’s arguments in the amicus about why Mexico’s permit denial is coherent with the precautionary principle as described in national and international law.

One tribunal member, however, disagreed. His dissenting opinion published with Procedural Order Nº 6 referenced the growing global dissent over the legitimacy of an arbitration system set up to privilege corporate interests. Arbitrator Philippe Sands, a law professor who specializes in environmental law, argued that the Cooperative’s concerns should be considered “in light of both (a) general legitimacy concerns in relation to investment treaty arbitration, and (b) specific local community interests that are engaged by a particular case.” He also argued that CIEL could “offer a unique perspective due to its ability to place this dispute in the context of broader debates and developments in international law.”

Most notably, he acknowledged how the ramifications of Odyssey’s arbitration could go far beyond this one project and cast a chill on environmental regulation in the country: “It is now well-recognized that investment treaty arbitration can have a significant impact on domestic regulatory regimes, even where compensation is the only remedy awarded. It is therefore entirely possible that a finding that the Respondent [Mexico] has breached the treaty could lead to regulatory changes which directly affect the interests of the Cooperativa, either immediately or in the future. The Majority’s decision fails to recognize or take account of the broader impacts of investment treaty arbitration.”

The Unviability of Seabed Mining and Investor State Arbitration

Just about everywhere that seabed mining projects have been proposed around the world, they have given rise to resistance from affected people and, as a result, a cautious approach from governments. As the amicus from the Puerto Chale Cooperative and CIEL describes, “Given the implicit dangers of developing seabed mining projects, authorities in most countries where this type of project has recently been proposed have refused permits or declared a moratorium on this type of activity.”

This is the precautionary principle at work, explains the amicus, which prescribes preventative measures to avoid harm to people and the environment “without having to wait for scientific proof of the cause-effect relationship.” The Northern Territory of Australia provides a clear example when in August 2021 it turned a 9-year moratorium on seabed mining to a total ban, citing the need to protect the coastal environment’s “substantial cultural, economic, biological and social value” and the inability to adequately assess or regulate the real risks from seabed mining.

The Investor State Dispute Settlement system enshrined in the original NAFTA and thousands of other International Investor Agreements around the world stands in direct opposition to the precautionary principle. Odyssey is just one of dozens of mining companies that are bringing multi-million or multi-billion dollar suits against governments, especially in the Global South, to extract profit when their projects fail for lack of social acceptance, violations of human rights, and great environmental risk.

The cost of such suits is not just monetary, as Sands acknowledges in his dissenting opinion, but can effectively pressure governments to weaken protections for people and the environment in order to settle or avoid future suits. At a time of overlapping health, economic and ecological crises, the time has come to undo this biased system that only has costs and no benefit to people or the planet.

Ellen Moore is the International Mining Campaigner for Earthworks and Jen Moore is an Associate Fellow of the Institute for Policy Studies. Originally published by Inequality.org.

Your Support Makes Our Work Possible

Earthworks helps families on the front lines of mining, drilling, and fracking. We use sound science to expose health, environmental, economic, social, and cultural impacts of mining and energy extraction. To support our efforts, please consider a tax-deductible donation today that will go toward our work reforming government policies, improving corporate practices, influencing investment decisions, and encouraging responsible materials sourcing and consumption.