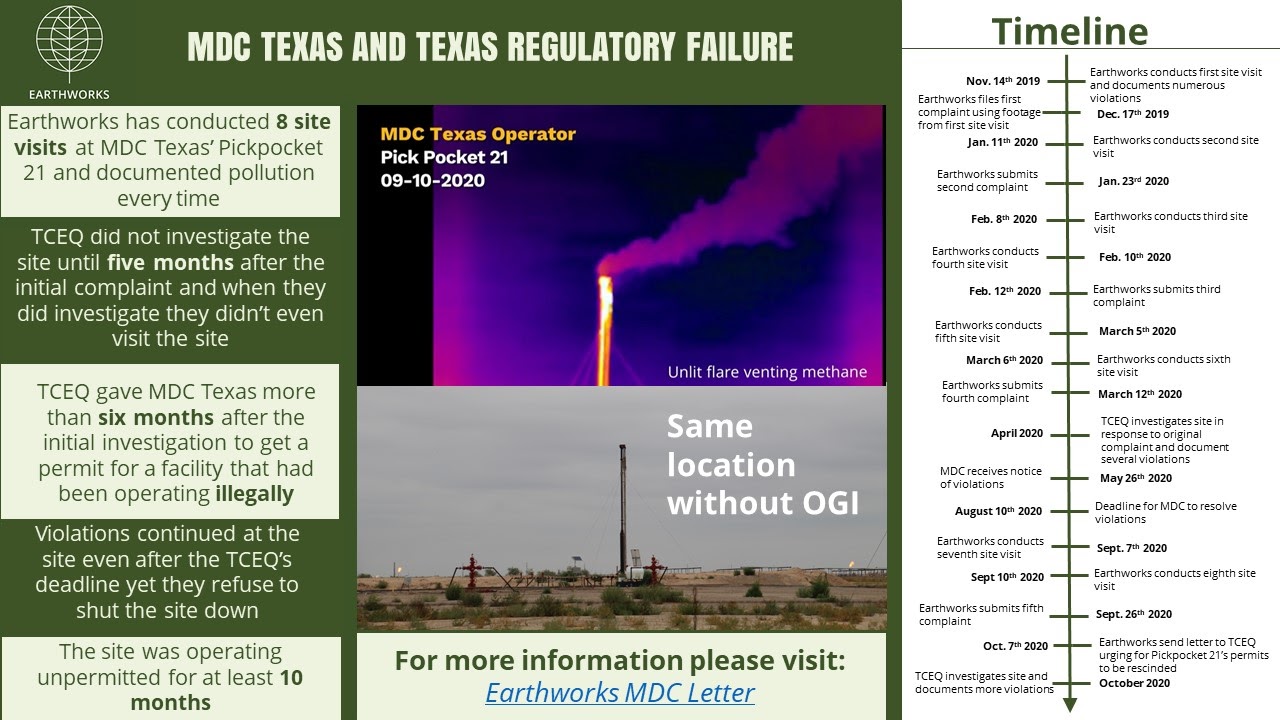

On October 8th, Earthworks sent an open letter to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) and Railroad Commission (RRC) outlining a history of misconduct at the MDC Pickpocket 21 drilling site. Earthworks’ certified optical gas imaging (OGI) thermographers had made eight field visits to the site over eleven months, documenting intense plumes of climate- and health-harming pollutants like methane and volatile organic compounds (VOC) pollution each time. As a result, Earthworks filed eight regulatory complaints .

It wasn’t until, four months after Earthworks initial complaint that the TCEQ “investigated” the site–not by actually physically visiting the site, but by simply doing a file review–and discovered that the operator did not have an air quality permit for the site. Despite this, TCEQ did not shutdown the the site. Instead, the operators were given more than three months to apply for the permit that they needed, during which time they continued to operate.

Yet even with that generous grace period, operators kept polluting. Earthworks visited again and discovered that emissions persisted.

The site is a perfect example of the systemic regulatory failures in the state of Texas. In two blogs, I’ll explain how TCEQ’s permitting and enforcement systems are effectively designed to fail.

Permitting

The oil and gas permitting process is supposed to ensure that sites meet both state and federal requirements related to air pollution. When a new site is built it requires an air quality permit. The permit determines the amount of pollutants the facility can emit.

Rather than having one office of permitting, the TCEQ houses different types of permits in different offices. Oil and Gas Permitting is housed within the Office of Air. There are several types of permits that the TCEQ uses. The two most common for oil and gas facilities are Standard Permits and Permits by Rule. Operators determine which permit their facility needs based on their own emissions estimates (higher emitting facilities generally require Standard Permits while lower polluting facilities use Permits by Rule) and then apply for approval of the permit by the TCEQ.

A third permit that is occasionally used by oil and facilities is a Flexible Permit, which allows the operators themselves to determine the emission caps of the permit and then submit it for approval by the TCEQ. These Flexible Permits were challenged by the EPA on the grounds that they are not compliant with the US Clean Air Act (one of the federal guidelines TCEQ permits exist to enforce), but a Federal Appeals Court forced them to reconsider and this permit type was upheld. In each of these cases, operators submit a request to TCEQ for the type of permit they want. The TCEQ is supposed to determine whether the permit type is appropriate and evaluate the emission reduction practices proposed by the facility. The current approval process, which relies heavily on data self-reported by operators, opens the door for TCEQ serving as a rubber stamp rather than a regulator. For example, in some cases the TCEQ has granted permits to operators stating that they will use “best practices” to reduce emissions despite the absence of any explanation of what those practices will be.

Pickpocket 21 was supposed to be a De Minimis Facility. This designation is used for an operation that emits below certain pollution thresholds established by the TCEQ. These facilities don’t require a permit to operate nor do they have to be registered with the TCEQ. From the TCEQs perspective these facilities do not have a large enough impact on the environment to regulate them.

Unfortunately, in a landscape dotted by thousands of well sites, even small amounts of pollution can add up to a significant impact. Since some of these sites aren’t registered with the TCEQ at all, it is difficult if not impossible to fully gauge the aggregate impact of De Minimis Facilities. In addition, operations like Pickpocket 21 can, despite operator claims, pollute more than the De Minimis limit. Since many of these sites are not registered with the TCEQ at all, when a site does surpass the De Minimis level there is little that can be done to hold them accountable.

As a result of Earthworks complaints, TCEQ determined this to be the case when it investigated Pickpocket 21. Despite operating the site without a permit and polluting above claimed levels, MDC was allowed to continue business as usual and given a grace period to get that permit. If you or I were caught driving without a license, you can bet there would be bigger consequences than just having to go get them. However, in TCEQ’s world, such basic rules often don’t apply to the oil and gas industry.