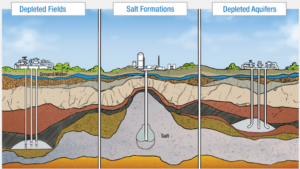

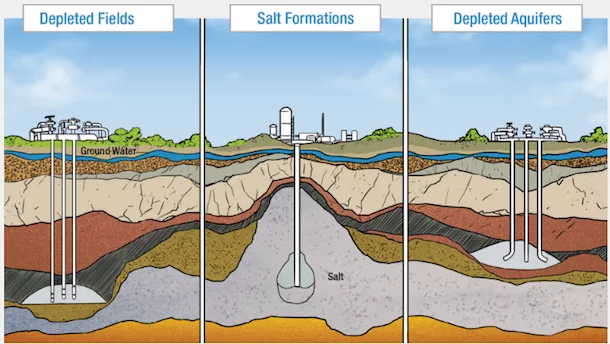

Natural gas consumption changes based upon economic conditions, weather, and price. To ensure adequate supply, utilities keep reserves in Underground Natural Gas Storage (UNGS) facilities. These include:

There are over 400 UNGS facilities nationwide, a total which hasn’t changed much even as gas production has increased. Between 2010-2015, total gas storage capacity grew only 5%, but the volume of gas withdrawn grew 9%.

This trend raises the concern that owners of UNGS facilities may be filling them to maximum capacity, resulting in very high pressures and a higher chance of leaks and explosions.

Air pollution and associated health impacts

No published research exists on air emissions specifically from UNGS facilities. However, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) collects greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions data; in 2015, operators reported that UNGS accounted for 1.5% of all GHG emissions from the natural gas sector. This figure is likely higher in reality, as operator estimates can be much lower than if their emissions were actually measured.

The main source of air pollution at storage fields is leakage from broken equipment or failed injection wells. The Aliso Canyon storage field leak took four months to cap, resulting in the largest single methane leak in US history—increasing California’s methane emissions by about 25%. It also led to the relocation of thousands of residents and health problems from volatile organic compounds and the mercaptan used to give gas a detectable odor.

In addition, compressor stations are often co-located at gas storage fields to re-pressurize the gas as it is injected and withdrawn from a field. These facilities emit methane and other pollutants from both normal operations and leaks in pipes and equipment.

Water pollution and associated health impacts

Over 40 years ago, EPA determined that UNGS facilities “present a potential for contamination of usable ground water” when gas leaks into surrounding soil or through rock formations. This can happen when gas injection and withdrawal wells are improperly constructed or plugged, or when storage areas are overpressurized.

In 2005, researchers confirmed this risk in a study showing that water wells clustered close to a storage field in Tioga County, Pennsylvania had higher concentrations of methane than others nearby. One hydrogeological analysis indicates that gas storage in salt caverns can push brine into water supplies.

Regulation

Environmental and health risks are made worse by the lack of clear and consistent regulatory oversight.

Federal safety standards apply to the above-ground pipes at UNGS facilities—but not “downhole” (underground) wells and equipment. The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) is responsible for UNGS facilities connected to interstate pipeline systems, but oversight for everything else is left to state agencies and utility commissions. This has resulted in a patchwork of regulations and practices, with many UNGS facilities left uninspected and unrepaired for years.

In response to the Aliso Canyon disaster, the Obama Administration appointed a task force to investigate safety problems with UNGS and recommend how to solve them. In late 2016, PHMSA issued a rule creating minimum federal safety standards for all parts of UNGS facilities and requiring inspections and maintenance by either PHMSA or state agencies. In the meantime, communities continue to call for the decommissioning and prohibition of gas storage fields.

For More Information

- Energy Information Administration overview of UNGS.

- Graphic and descriptions of underground natural gas storage.

- Earthworks overview of the Aliso Canyon disaster and its impacts.

- Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration 2016 rule to improve at UNGS facilities.

- Inside Climate News report on UNGS regulation.

- Earthworks case study on environmental impacts on residents near a Pennsylvania gas storage field.