Episode 1: Welcome to Methane Land

Episode 1: Welcome to Methane Land

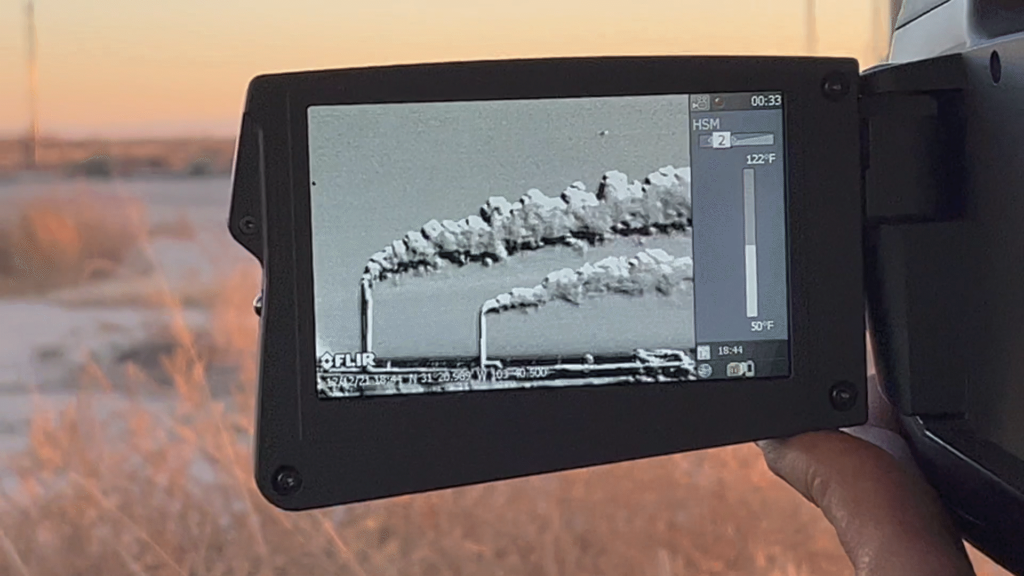

The Permian Basin oilfield in West Texas is destroying the climate. The Texas Field Team at Earthworks document oil and gas emissions with technology that makes pollution invisible to the naked eye visible.

Listen and subscribe now via Apple, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Amazon Music, Podcast Index, Stitcher, Pandora, TuneIn, Deezer, or iHeartRadio.

Guests

Sharon Wilson is a 5th generation Texan who worked for the oil and gas industry in Ft. Worth, but was unaware of any environmental issues. After 12 years, she left the industry and bought 42 acres in Wise County adjacent to the LBJ National Grasslands. Unknown to her at the time was that George Mitchell was experimenting in Wise County to figure out how to produce oil and gas from shale. She had a ringside seat at the sneak preview called Fracking Impacts. As she watched her air turn brown and, eventually, her water turn black she documented it all on her blog texassharon.com. Sharon and her son moved to Denton, Texas thinking the city would provide more protection. That irony still burns, but it brought her life’s work with Earthworks’ Oil & Gas Accountability Project in 2010. Sharon has briefed NATO Parliamentary Assembly, EPA regulators and even former Administrator Gina McCarthy on the impacts of oil and gas extraction. In 2014, she became a certified optical gas imaging thermographer and now travels across the U.S. making visible the invisible methane pollution from oil and gas facilities and giving tours to media, Members of Congress, state lawmakers, regulators, and investment bankers.

Episode Transcript

(music)

Miguel Escoto (host): From the Fort Davis Mountains in West Texas, the sky actually has a decent amount of stars. It is striking and beautiful. In a region surrounded by dusty, smelly, noisy oil and gas extraction, the green, calm hills of Fort Davis are an oasis. It’s home to the world-famous McDonald Observatory, an astronomy research center with mega telescopes that have made important scientific discoveries. Once home to the second largest telescope in the world in the 1930s, the location was chosen because of its dark, star-soaked skies. But much has changed since 1939, the heyday of this observatory. Notably: light pollution from oil and gas.

(sounds of being outside)

Sharon Wilson: But see how bright the horizon is right there? All that is light pollution. And that’s the way it started at our place.

Miguel Escoto: Sharon Wilson tells us about stargazing with her son Adam in her ranch in Wise County, Texas during the mid 2000s.

Sharon Wilson: You know, we were really poor as far as money, but we had this beautiful land and all these incredible animals and we would, at night, on a night like this, we would drive the pickup truck out into the pasture and I would let Adam have a Coke—which I didn’t let him have very often. And we’d cook popcorn and I had chocolate, hot chocolate with Rumple Minze—extra hot chocolate—and all the horses would come and they would stick their heads over the bed. You know, they just wanted to be with us. And the dogs would be there, and the cats would come, and the goats would come and we would just look at the stars and talk about the constellations and the mythology. And the coyotes would be yipping. But, you know, when he was growing up and we didn’t have a lot of money to go spend on doing things, we had books. And I would take a piece of construction paper and trace the constellations and use a pin, a safety pin and poke holes in it and put it up in the window so that we could familiarize ourselves with the constellation, and then we would go out at night and find that constellation.

Miguel Escoto: Sharon didn’t know it at the time, but Wise County would become the birthplace of a global fracking boom. This is where George Mitchell, dubbed the “father of fracking,” experimented with hydraulic fracturing as a method of extracting oil and gas through horizontal drilling. They drilled on Sharon’s property, ultimately ushering in a nightmare of impacts. Her air turned black. Her water turned brown. However, the first sign of the pain that would follow was some light in the distant horizon.

Sharon Wilson: But then this encroachment of light pollution…. It just got bigger and bigger and bigger until all the stars were so faint. And that’s when Adam wrote this essay and said, “They murdered the stars.”

(music, sounds of Donald Trump and Joe Biden debating)

Miguel Escoto: ‘Murdering stars’ is a good way to capture that geological, astronomical, existential climate crisis that is the Permian Basin. Simply put, West Texas will determine the fate of the world. What happens here in the next decade will reverberate throughout history. This is because the region is blessed and cursed with the Permian Basin Shale, named after the rock and fossil deposits dating back millions of years during the Permian Geological period. The Permian Basin is a 6,000 square foot area, roughly the size of Britain, that sprawls through West Texas and Southeast New Mexico. It is one of the largest producing oil and gas regions in the world, accounting for nearly 30% of all U.S. oil production. This is the fracking epicenter of America. It is where Donald Trump rose up to during the 2020 election to scoop up 7 million campaign dollars from the oil and gas industry.

(music)

As of early 2022, amid an ongoing climate crisis, the U.S. Energy Information Administration calculates that the Permian produces about 5 million barrels of oil per day—more than any other shale in the United States. It also calculates that the region extracts about 18 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day. Again, emphasis on the “per day” part of those statistics. Okay. But let’s put these numbers into perspective. Imagine enough oil to fill up a common Coke can. If you stack these cans end-to-end with 5 million barrels worth of oil, your cans would extend to 206,342 miles, roughly enough to circle the Earth eight times. So the Permian produces enough oil to circle the Earth eight times every day.

(music)

Unfortunately, production levels at the Permian are only projected to grow. Companies are continuing to drill, frack and produce. According to the website and report PermianClimateBomb.org, oil production is projected to grow 50% from 2021 to 2030. Natural gas liquids, or NGL production levels, are also horrifying. Based on data analysis from Rystad Energy, Oil Change International calculates that Permian production is going to increase by 60% in the next nine years, surpassing gas liquid productions of every other country in the world: Saudi Arabia, Russia, Qatar, Canada and the United Arab Emirates.

But what does this all mean for the health of communities that live on the ground? What does this mean for the planet? Well, for communities on the ground, it means increased rates of asthma, respiratory illness, birth defects and even cancers. Oil and gas production emits a type of pollution called volatile organic compounds, or VOCs. These include benzene, toluene, formaldehyde, and other ozone precursors which have serious health impacts for those on the ground. Let’s look at emission levels of some towns at the heart of the Permian Basin: Midland and Odessa, Texas. According to the Texas government’s own measurements, the Midland-Odessa area is responsible for more VOC emissions than Dallas, Fort Worth, and Houston combined. Now, anyone from Texas can immediately understand how outrageous this sounds. But for context, Midland-Odessa’s population is about 348,000. The population of DFW and Houston are collectively about 10 million people. And Houston has its own share of extreme VOC emissions, being home to some of the worst refineries in the U.S. But communities in the Permian are not the polluters. We are being polluted by a Wall Street funded fossil fuel machine. Every barrel of oil produced, every cubic foot of gas fracked, means pollution for those of us in the region.

But how do Permian oil and gas production levels affect the climate, the world? In a single word: methane. Methane is a greenhouse gas about 86 times more powerful at warming the climate than carbon dioxide. It is a byproduct of oil and gas production. In the Permian, studies estimate that as much as 3.7% of gas production is being vented—released—into the atmosphere. This amount of methane is the equivalent of filling up the Atlantic Ocean every 55 days. It is no surprise that scientists using satellites from space can spot gargantuan clouds of greenhouse gasses hovering over the Permian, the equivalent of 1.7 million metric tons.

(music)

The Permian has been called the home of the first rodeo, but it’s also the heart of American oil country, the epicenter of fracking, the global climate bomb, and methane land. Yes, it is a network of small towns, but it is also a powerhouse holding up the fossil fuel industry on its shoulders. So what can be done about this giant? How can we dismantle this climate catastrophe and protect the boom and bust towns caught in the crosshairs? Well, there’s no silver bullet. Victory will require a mass movement with a variety of tactics. It will require thousands and millions of us to stand up and pressure politicians and corporations to stop producing fossil fuels and transition to clean, renewable energy. It will require exposing the oil and gas industry for their climate-destroying processes of extracting oil and gas from the ground and exposing the oil and gas industry. Specifically, the Texas Permian Shale will be the focus of this show. Our podcast series will walk you through the mission of a group of activists with the environmental organization Earthworks. So I present to you my colleagues at the Texas team.

Sharon Wilson: I’m Sharon Wilson, and I’m senior field advocate for Earthworks.

Miguel Escoto: Sharon Wilson is a seasoned fossil fuel hellraiser, a frontline fighter and a certified optical gas imaging thermographer who has been sued twice unsuccessfully by the oil and gas industry and who has been personally blocked by Exxon on Twitter.

Jack McDonald: Hi, I’m Jack McDonald. I am the Texas Field Analyst for Earthworks.

Miguel Escoto: Jack McDonald, 19 years old, is a research extraordinaire and flaring expert who has publicly sparred with Texas state environmental agencies about their flawed flaring data. Jack won every time.

(noise from being in the field)

My name is Miguel Escoto. I am the West Texas Field Associate with Earthworks. We arrived to methane land on March of 2021.

(music)

At Earthworks, we go directly into the oil fields to document emissions from oil and gas sites using optical gas imaging technology. This is a camera which allows you to see greenhouse gasses and VOC pollution, which would otherwise be invisible. It’s a technology used by government regulators and the industry themselves. Armed with this camera, we visit oil and gas sites. We park near the side of public roads and point the OGI technology at flares, tanks, compressor stations, gas plants and pipelines in the field to see if we can detect methane and VOC emissions.

(noise from using the camera in the field)

Miguel Escoto: So can you tell us really briefly what we’re seeing here at this Primex site?

Sharon Wilson: It’s a really dirty flare. It’s putting out a lot of pollution. It’s not combusting the emissions like it should be.

Jack McDonald (via two-way radio): Is there a car coming up on the road right now?

Miguel Escoto (via two-way radio): That was the same guy, huh?

(noise from two-way radio)

Miguel Escoto: We’re currently pulled off to the shoulder of this public road next to the Primex site. There is the same red truck that was harassing us. This red truck is now pulling up to where Sharon is and is taking video of what we’re doing. What we’re doing is totally legal.

Jack McDonald: Yeah. So we were out here on this fully paved, painted county road, and a Primex employee came out, followed us in his pickup truck, pulled off the road and came over to us and told us we needed to leave. And I was going back and forth with him saying, “this is a public road… your site is visible from a public road, so there’s no presumption of privacy.” And he started talking and I will try to relay what he said, but it’s actually hard to explain because I didn’t fully understand what his point was. He started talking about Earthworks and the economy and OGI being nonsense and all this stuff, and eventually I was just like, it’s a public road. His ultimate legal argument for why we needed to leave was ‘You cannot take photos from a public road unless you were hired to do so.’ And because Earthworks is a nonprofit, somehow, in his mind, that meant we couldn’t be taking video. Sharon drove down the road, took photos at another site. He followed us, continued harassing us until ultimately he just pulled off when Sharon showed that she was recording him.

Miguel Escoto: Sharon, you intimidated him quite a bit because he seemed flustered after he spoke with you and the reporter from Scientific American. So… what did you do? How did you get him to stop harassing us?

Sharon Wilson: I think he didn’t want me to take a video of him acting like a fool and trying to threaten us and to get us to leave. So basically that’s it, you know, he put his hand in front of my camera and actually touched my lens, which wasn’t at all cool. He was very agitated.

Jack McDonald: The irony of the whole thing is when he confronted Sharon, we weren’t even at a Primex site… he was a Primex employee trying to protect another operator’s site.

Miguel Escoto: Polluter solidarity.

(laughter, noise from being in the field)

Sharon Wilson: So, they’re only permitted to release a certain amount, but no one ever checks to see how much they’re releasing. When I first stopped, it was a lot. Now it’s just if you move this, if you move this a little bit and you can see better how much it is, but the wind is changed. And yeah, they can’t seem to keep three flares lit. They can’t operate. Look. Look at that. That’s black carbon, it is very damaging to the climate. They can’t keep them lit. They can’t operate them properly. They can’t stop the emissions from the tanks. They really suck at doing this. They suck. They need to stop.

(music)

Miguel Escoto: Finding blasting methane emissions at these sites is the usual, not the exception. Although the media usually describes these sorts of emission events at the oil fields as methane “leaks”, the more accurate term is methane releases. The pollution we see is part of the industry’s intentional releases of emissions to maximize profits and productivity. It looks more like a blasting firehose than a dripping faucet. When we capture pollution events, we submit official complaints to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, the TCEQ. This is the state’s environmental agency tasked with regulating oil and gas. While most of the pollution we detect is technically a violation, industry has a menu of loopholes they can call upon to justify their pollution. The TCEQ is legally obligated to review the video complaints we submit. However, many times we find that their “investigations” consist of nothing more than the government emailing the company a survey to fill out.

Sharon Wilson: We have two agencies that permit oil and gas, and the Railroad Commission permits the drilling and flaring and the TCEQ permits the pollution. But… It’s ridiculous because the industry doesn’t get permits and nobody knows unless we, Earthworks, catch them. And we do catch them. But to get a permit, if you want to get the lowest level of permit, which is a permit by rule, you have to list the equipment you’re going to have on the site. Well, the manufacturer wants to market their equipment as a low-emissions equipment so they calculate what their piece of equipment is going to emit. No one measures that to see that it’s really accurate. Then the industry hires a petroleum engineer and says, I want to have this site and I want this equipment on it. And the petroleum engineer makes the calculations fit within the permit levels. Whatever it takes, they calculate it so that it works. And no one actually ever measures any of the emissions to see if the industry is staying within their emission limits. There are so many ways that the regulatory agency does not keep up with the permits. They need to just stop. They need to stop permitting, period.

Jack McDonald: So I’ve been spending a lot of time digging into what’s referred to as an H9. It’s governed by Rule 36 of the Railroad Commission, which I know just sounds like number salad… Rule 36 is basically the guideline by the Railroad Commission that governs sour gas, that’s any gas that contains above, I believe, it’s 100 parts per million hydrogen sulfide. And hydrogen sulfide is a really nasty, nasty, poisonous gas. It can kill people. It can cause all kinds of problems. Short term exposure in high concentrations can cause nerve damage. And basically what it’s supposed to happen is not every well actually produces sour gas. Some produce what’s called sweet gas—there’s no hydrogen sulfide. But all of the wells that produce sour gas are supposed to test their wells to see how much sour gas they’re producing. For instance, for some wells it might be 100, 200, 300. Wherever it lands based on that testing, they then get put into different regulatory categories, like you may need to have an extra compliance plan or an emergency alarm system based on how high your hydrogen sulfide concentration is coming out of your well. And what I found going through a series of different operators and looking at the H9, which is the actual form via which that test is submitted, is that massive chunks of operators just fail to submit those H9. Operators, sometimes 40% or more of their wells, just do not have an H9 at all. And that’s really concerning to see such a dangerous gas being totally disregarded.

Sharon Wilson: And so thinking about that, it is voluntarily-submitted information. The regulatory agency does not go out and check these wells to see if they need a special permit to produce this deadly gas. They leave it up to the operator to admit whether or not they produce this gas. The operator knows that if they admit it, they’re going to have to have more equipment and stricter regulations. So… I don’t know. Do you admit when you’ve had one too many beers and you drive home?

(laughter)

Jack McDonald: I feel like a big part of that is it goes back to this thing of just profound arrogance on the part of operators that the permits that do exist are pretty lackluster. I have thoughts about the regulatory categories that H9 puts you into… I don’t think they’re sufficient. But these operators are so profoundly arrogant that they don’t even bother to follow the lackluster regulations. Like going back to what Sharon is talking about, how there’s so many loopholes in these permits, and then seeing the number of operators who don’t even bother to get a permit when they have access to all those loopholes. It’s just crazy.

Miguel Escoto: It is exceedingly rare for the TCEQ to issue a notice of violation to oil and gas companies because of the extensive range of loopholes that industry benefits from. According to a study by Environment Texas, less than 3% of emissions violations drew any penalties from TCEQ or the state of Texas. A slap on the wrist considering the millions in profits of these companies. Episode two and three of this podcast will dive deeply into the permitting loophole extravaganza that is environmental policy in Texas and the pitiful, virtually non-existent levels of environmental regulation enforcement at these oil fields. While we don’t trust the TCEQ to do its job, documenting oil field pollution and submitting these complaints is nonetheless important. We’re able to file public information requests from the TCEQ to learn about the extensive inadequacies of Texas state regulators. We’re able to witness exactly how captured the state government is by these oil and gas industries. Plus, visualizing oilfield pollution with your own eyes is powerful. We use these images of methane blasting into the atmosphere to warn the public about fracking, to mobilize advocates, and to support fenceline communities dealing with this pollution. One example of fenceline communities impacted by oil and gas expansion is Jim and Sue Franklin.

(noise from the field)

Miguel Escoto: Where are we standing right now? Why is that so important?

Sharon Wilson: This is where Sue and Jim Franklin used to live.

Miguel Escoto: So Jim and Sue Franklin were about how many feet away from this Primex site that we see here?

Sharon Wilson: They didn’t drill that one until they bought Jim and Sue out, but they drilled this one. And I would say maybe it is a little more than a football field… maybe at the most 200 yards at the most from their house.

Miguel Escoto: Did the Franklins feel any health impacts?

Sharon Wilson: Oh, yeah, they got very sick. They felt health impacts with that first well down there and then from the ones on the other side. And then they put this one right across the street. So they had a lot of health impacts and Sue was very sick, had to actually move to town and live in town. And Jim stayed out here.

Miguel Escoto: On our trip, we visit Sue Franklin at the Davis Mountain Rock Shop in Fort Davis, Texas.

(noises from the rock shop)

Sue Franklin: I haven’t seen anything or what the one on my property is emitting now, but it’s because I haven’t been there. I mean, it’s been a long time since we’ve seen each other. I started getting really ill, having problems breathing. And I kept going to the doctor and he kind of told me—because I told him I was living there—that I was having a problem, a little problem, feeling like I couldn’t quite breathe right and he told me to just take an allergy pill. Then I went back and I told him, you know, I don’t know what asthma feels like, but sometimes I just feel I can’t get a breath in. And he told me at that point, he put me on—it’s called Montelukast. And it’s, I don’t know exactly what it does, but it helps clear your lungs so you can breathe. I had nothing before that. I had nothing before that. I always was fine as far as breathing. No allergies. And the other thing is the headaches, you know, that caused severe headaches for both me and my husband. In the morning we would wake up and we just couldn’t function. We wanted to crawl back in bed and just lay in it. But we would usually get ourselves up and out as quick as we could. And then half the time you’re laying there and you smell it in your house. But when you open the door and it hits you in the face, it was like… run! She took me to that one site that was just a pump station, and they had a big tank sitting there. And she got out, took a picture of it, and there was this huge cloud coming from just those tanks, that’s not the wells or anything that was going straight to Balmorhea. It was blown right over on the town. And it’s like they think they have it all in their own area, it’s all controlled, but none of it is controlled. My husband is at home in bed right now. He’s having difficulties with his back. He’s having back pain. And Wednesday morning, we’re going to Odessa for injections in his back. So he’s been doing bad. I told him today he was sitting in his head, his desk back there, and he kept falling asleep. And I just finally told him, go home. Just go home. And he slept all afternoon. So I don’t know.

Sharon Wilson: Their health has not recovered.

Sue Franklin: No.

Sharon Wilson: Since they moved out of it their health has not recovered.

Sue Franklin: And never will. It never will. My breathing has not recovered. I take the medication every day. It’s been a rough battle for us. Very rough battle. We’ll never quite recover. We’re happy where we’re at now. And we have this little store up here away from it. I never have to go, unless I have to go to Odessa. Then I have to go in the smell again. And when you go down in the daylight, when you go over the hill by old Rose Pass and you just just come up over that hill and you see that brown haze hanging over the whole valley, it just makes you not want to go.

(music)

Miguel Escoto: So after about a week of fieldwork, I sat down with Sharon and Jack to debrief on what we witnessed. What were your general reactions from what we saw?

Sharon Wilson: Well, in the face of rapidly accelerating climate change, it’s hard to fathom what’s happening, and it’s hard to feel hopeful that we’ll be able to stop it in time. But it also makes me very angry. And that’s a better action emotion for me. And, you know, it’s the same thing that I witnessed when I worked for the oil and gas industry. The intense, outrageous arrogance and entitlement that they have, it’s psychopathic.

Jack McDonald: Yeah. I mean, like, it was crazy. This was my first time actually being out in the field and finally being able to kind of put faces to names in terms of seeing some of these sites and understanding these crazy chains of emission events and complaints and emission events and complaints. And then nothing happens. And the site looks exactly the same as it did last time. The same issues. That kind of stuff is just crazy to me to watch these sites, just see these sites not really improve. Like to go out there and see sites that I know for a fact we’ve made complaints on in the past and nothing changes. That’s just so profoundly depressing to see that the government really doesn’t seem to care.

Miguel Escoto: One of the things that really impacted me this time around that hadn’t on my other previous field trips is how normalized everything is and how there’s almost like a rhythm to everything and how the city of Pecos and all of the oil and gas workers that go visit sites while we’re taking photos… if you look at it from a certain angle, it’s even boring what we’re seeing, right, these ugly pieces of machinery that are miles and miles apart across a flat, barren desert. It kind of looks boring. But if you add that context of what those emissions mean to the world, it isn’t boring. It’s actually extremely infuriating. So, yeah, that was one of my reactions. Just like how it is business-as-usual everything was. Even when I mean… we have a new president, right? There’s a new government. Trump is no longer there, but there was virtually no change. And the way I saw it… What do you think, Sharon?

Sharon Wilson: There’s no change, and it’s worse. They’re ramping things up again. And the thing that’s so discouraging is we can’t even physically document and make complaints on everything we see. We have to do triage and decide what is the worst and just ignore the rest because we just physically cannot cover it all.

Miguel Escoto: I also asked them what this ground we stood on means to the world. What is the importance of the Permian?

Sharon Wilson: Well, I guess the importance of the Permian Basin depends on who you are. To the oil and gas industry, they think it’s money and they justify what they do by talking about the economy. To me, it’s something that has to be stopped. It has to be stopped immediately because there will not be a livable planet for the future if the Permian Basin continues at the rate that they have planned, there won’t be a livable future.

Jack McDonald: Yeah, I mean, I feel like it’s almost a pretty objective question in terms of what it means to the oil and gas economy — it’s such a big part of that industry. And like Shraron said, if you’re the oil and gas industry, you view it as a big cash cow. If you’re someone concerned about the climate, then it’s a massive concern that needs to be stopped.

Miguel Escoto: Next, we discuss what we think about Texas’ policy on methane in the oil fields. More accurately, we react to the fact that Texas refuses to even count methane.

Sharon Wilson: Texas does not regulate methane. They don’t care about methane. They have vowed to never regulate methane. So when an oil and gas operator submits their emissions for an emission event or their emissions calculation for the year, that does not include methane. They get to subtract methane from that calculation. Actually, that is criminal at this point where we are in climate change. It is so ignorant and backward and it’s just criminal. And the reason that it happens is because the oil and gas industry showers our government with money and their ears are so stuffed with oil and gas money that they can’t listen to logic, reason or science.

Miguel Escoto: I agree. I agree 100% with that, Sharon. And… I think it demonstrates how radically unjust TCEQ is. And it’s the perfect example of the overhauling transformational shift that needs to happen in the state government. We don’t have to point to anything else, but we will and we do.

Jack McDonald: I think one of the other interesting angles in this is if you take the natural gas oil industry at their word that natural gas is this amazing bridge fuel, it’s going to be the thing that solves everything, it’s the perfect energy source. Even then, it becomes hard to justify the fact that methane isn’t regulated because we’re basically dumping a at least ostensibly valuable natural resource straight into the atmosphere. Like, I think we should not be like extracting and using oil and gas, but if we’re going to extract it, we may as well actually use it. EDF has data that says that Texas actually flares off more natural gas and the entire state consumes in a year. And that kind of data is just insane to me that this ostensibly valuable resource is jettisoned into the air for virtually no reason and the government doesn’t do anything to stop it.

(music)

Sharon Wilson: And this is such a precious, precious part of Texas, the best Texas has to offer. This area down through Marfa and the Big Bend is so beautiful. It’s the crown jewel. Well, from Balmorhea to here to Marfa to Big Bend and all in Marathon and all those areas. So beautiful. When I started working out here for the Permian Basin was in 2016 and you could see the mountains pretty vividly and you saw how it was today. It’s covered in smog. And that’s from all that, the particulate matter and the ozone and all the pollution is creating smog that obscures the mountains. And you can see it hanging in these little pockets in the mountains.

Jack McDonald: That was one of the things that I noticed being down in Pecos. It doesn’t feel like the air quality there is bad. Like, you know it is intellectually, but it doesn’t feel like it until you start looking at something like the mountains where you can just see this haze of smog over everything.

Sharon Wilson: Or until you walk out of your hotel and you smell the hydrocarbons.

Jack McDonald: When the wind changes. Yeah. And you just like it hits you like a brick or anything.

(music)

Miguel Escoto: Well, that’s it for right now. But later in this series, we will highlight some stories of frontline community members resisting pollution. We will explore the radioactive waste water crisis that fracking imposes on the region. We will do a deep dive into the permitting and enforcement corruption process of the Texas state government and we’ll sit down with experts to discuss how a transition to clean, renewable energy can be a job-creator for the region and how we can actually benefit workers currently stuck in the oil and gas sector. Until next time, stay outraged.

(music)

Miguel Escoto: Ever since you said that phrase, “they murdered the stars”, I haven’t stopped thinking about it.

Sharon Wilson: Yeah. That’s not all they murdered… Oh lord. They murdered my water, too.

Defuse this Climate Bomb!

We must act now to stop the Permian Climate Bomb and save the planet for future generations.