Notes from the Field: Mexico, 9-14 October 2023

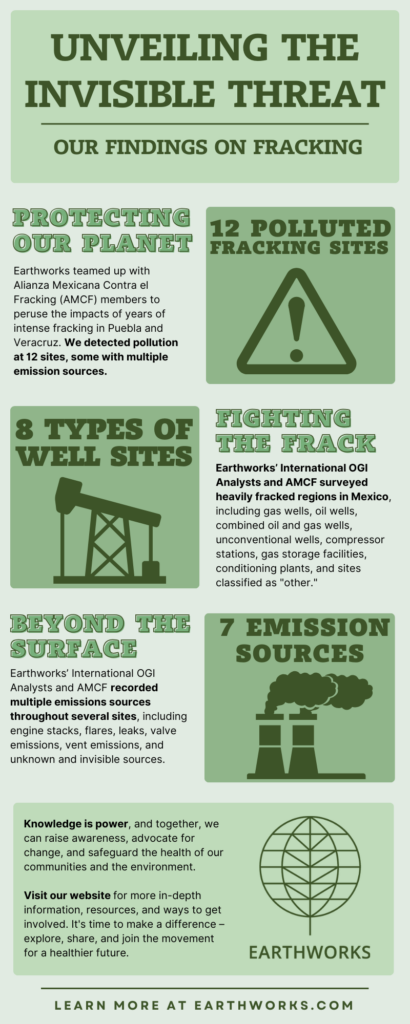

During the week of October 9-14, 2023 Earthworks teamed up with members of the Mexican Alliance against Fracking (Alianza Mexicana contra el Fracking, AMCF) to peruse the impacts of years of intense fracking in Puebla and Veracruz.

As an International OGI (Optical Gas Imaging) Advocate and Analyst for Earthworks, I traveled to Mexico City with the FLIR GF320 camera on hand to survey this region that is the most heavily fracked in Mexico. That region runs alongside the Burgos Basin near the northern border in Tamaulipas and other states which we couldn’t survey due to safety concerns. We were joined by the AMCF and also two members of Televisa. The optical gas cameras use state of the art technology to visualize air pollution (methane and other gasses) from the oil and gas industry.

Background on Fracking in Mexico

Fracking is a drilling technique that uses millions of gallons of water, dangerous chemicals and sand to extract oil and gas trapped in shale stone deep in the subsoil.

Fracking has been practiced by PEMEX for at least 17 years already. Although President Andrés Manuel López-Obrador made a promise during the campaign leading up to his presidency that he would ban fracking during his tenure, it has not been officially prohibited or banned in Mexico. “We will no longer use methods to extract petroleum that affect nature and exhaust the water springs, like fracking,” he said in March 2018.

This impasse around fracking in Mexico merits comparison on the one hand with situations in other countries, especially Colombia. There, proposed legislation around a fracking ban is supported by its President Gustavo Petro and by the Colombia Free of Fracking Alliance. It is currently awaiting a third round of debate in Congress, and spurring much conversation around the need to solidify plans for a truly just energy transition. On the other hand, there is also the steadfast support from government officials in Neuquen and at the federal level in Buenos Aires (Argentina) for an expansion of fracking in the Vaca Muerta Shale formation in Neuquen and Rio Negro provinces with dire consequences for indigenous and non-indigenous communities in resistance.

Today, the Mexican Alliance against Fracking hopes that López-Obrador will keep his promise to ban the practice for good.

There are recent indications that support for fracking by his administration has increased. The National Hydrocarbons Commission (CNH) announced that Mexico produces 190,000 barrels/day of fracked oil, which is approximately 10% of the 1.9 billion barrels/day that has been the average production in Mexico since 2019. PEMEX significantly increased expenditures on fracking in 2022 (more than 200% more than 2021), although that was reduced by half in 2023, with ups and downs in terms of how much of the budget is used. There is a recent announcement from Security, Energy and Environment Agency (ASEA) Director Angel Carrizalez Lopez that ASEA safety and environmental regulations would curb the impact of fracking on drinking water.

This possible backsliding away from a ban has dire consequences, especially for local communities, as they are among the ones feeling the brunt of the health and climate impacts.

Our Findings

Nearly all of the fracking wells we visited had visibly concerning incidents of air pollution. When oil & gas operations pollute, they release methane gas but also volatile organic compounds (VOCs) like benzene, ethyl-benzene (both carcinogenic), toluene, xylene, propane (all highly toxic and causing of developmental, neurological, and respiratory problems). According to a recent CartoCritica longitudinal health study from hundreds of cases between 2017-2023, the residential proximity of pregnant women to gas wells in the municipality of Burgos was strongly linked to more than ten congenital and genetic developmental health impacts in newborns.

At the same time, oil & gas pollution has major consequences for climate. Methane gas is more than 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide at warming the atmosphere. It is inextricably linked to climate warming, especially at the levels reported in these 12 pollution events captured by satellite images during 2019-2022 in Veracruz and Puebla. It has also been reported that the Mexican government significantly under-reports methane releases, and that the reality can be as much as ten times more than the official estimates. Adding to the harms, fracking is connected to water contamination and earthquakes, with one report stating that 304 earthquakes in the state of Nuevo León in a ten year period were directly linked to fracking.

One of the organizations that is part of the Alliance is the Regional Coordinator of Solidarity Action in Defense of Huastecan-Totonacapan Territory (Corason) formed in 2015. They support and highlight community concerns, such as that from the community of El Tablón, Puebla, where people started developing health problems such as nausea, headaches, and vomiting from fumes from the nearby Pemex’s Pankiwi well in March 2019. Four years later, these impacts are still felt, despite maybe in a more dispersed way. The well seems now to be not in operation, but we documented fugitive emissions from one of the fracked oil wells. These and the many other emissions found have worrisome consequences for the health of the communities and the proximity of the orange and other crops being produced by El Tablón community members in the surrounding of Pankiwi well.

One of the most intense findings was the sheer level of open-air exposed contamination from crude oil, which is something I haven’t seen so pervasively in other countries I have visited for OGI surveys. It is as if the norm among PEMEX sites is leaving oil dripping from enclosed combustion containers, sitting idly at the bottom of productive and abandoned gas wells, around the gas well cylinders, in piles of contaminated soil after dangerous explosions and spills, or intensely black crude filling up water wells where people used for their drinking water. Below are some of the photos we took of spills or contamination we encountered.

Most rural residents we spoke to had little if any access to water, and in many places they depended on buying plastic water bottles for drinking and water brought in by tanks for house and irrigation use.

Our biggest conclusion from the trip is this: Coupling our recent findings with the fact Mexico already has regulations in place to control methane emissions since 2018, we believe it to be highly unlikely that newly government-proposed water safety, emissions regulations, or fines for company violations will work, even if they were to be implemented. It is clear that the Mexican government has failed to enforce. What would work? The fracking ban President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has promised.