The web of regulations that govern oil and gas operators can be complicated. One of the most complicated aspects of that regulatory apparatus is the Texas Environmental, Health, and Safety Audit Privilege Act (the Audit Act). This 1995 law was designed to create an incentive system for regulated entities to self-report violations so that regulators could in turn enforce the law better.

The Audit Act covers numerous state agencies, including the agency one that oversees oil and gas operations, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). At the TCEQ, the Audit Act allows operators to skirt accountability from regulations rather than increasing it.

For an operator, the process of utilizing the Audit Act is very straightforward. The operator sends a notification of an audit (NOA) to the TCEQ saying that they plan on conducting an audit of their site for any possible violations, including the timing and scope.Then, they conduct an audit of the site and document any violations they find. A report of any violations they find is then sent to the TCEQ via a Disclosure of Violation (DOV) along with a plan in order to resolve the violation in a “reasonable time”. The TCEQ is responsible for both determining whether the corrective action will resolve the violation and determining what a “reasonable time” means. Notably, the operator-friendly flexibility of the Audit Act doesn’t apply if TCEQ has already found the violation another way (for example, due to a complaint or a standard site investigation).

In return for following this process the operator gets two things. First, the TCEQ grants limited immunity to the operator for the violation. This means that the TCEQ will not levy fines against operators for violations self-disclosed in an Audit. The TCEQ may still order the operator to do things to resolve the violation (for example installing pollution control equipment) . The second incentive is that some of the information in the audit becomes legally “privileged”. This means that that information is generally not available to the public or even other state agencies–further decreasing operator accountability. Even more concerning, this privileged status prevents even TCEQ from accessing violation information from audits when assessing an operator’s reliability or reviewing permit applications.

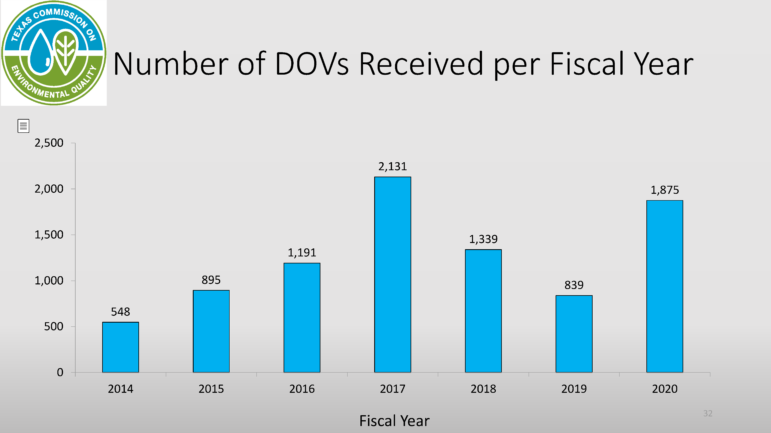

According to a TCEQ presentation, nearly 2,000 violations skirted fines for violations using the Audit Act just in 2020:

There are a few limited checks on immunity, for example if an operator was aware of violations before conducting an audit. . How this is determined is unclear, but the TCEQ stated during their Audit Act presentation that one of the most common DOVs is for lacking permits for a site that the operator oversees. How an operator could be unaware that their own site lacks a permit is vague. Operators also may not be granted immunity if the violation poses a present danger to health and the environment. Yet again, it’s unclear how that danger is defined and enforced, although by TCEQ’s own admission this provision is rarely used. Finally, supposedly operators can’t use audits to avoid repeated or continuous violations.

According to the TCEQ’s Audit Act presentation, the Audit Act process exists to encourage operators to stay in compliance with regulations that are too time intensive or too complicated for the TCEQ to enforce. This is why the violation has to be something the TCEQ is not aware of, because in theory simpler violations would be caught by the TCEQ and therefore not eligible for the Audit Act. That alone should raise questions about TCEQ’s ability to oversee the operations it permits and enforce the regulations it is mandated to. For years, Earthworks has documented how the TCEQ routinely fails to issue violations for even basic problems. Giving operators another way to skirt regulatory enforcement is illogical–and risky for the environment and frontline communities.

What Texas really needs is robust enforcement by a public agency, not self-policing by polluters. .