Experiences from a recent trip to the Dominican Republic

In November of 2022, I traveled to the Dominican Republic, with representatives from MiningWatch Canada and the NYU Global Justice Clinic to learn more about the impacts of Barrick Gold’s Pueblo Viejo mine on local communities, as well as to understand how communities are advocating for remedy for the environmental and human rights abuses committed by the company.

I was impressed by the organizing capacity and strength of the local communities to demand remedy for their rights and propose solutions to the problems created by decades of mining. And I was disappointed by the lack of transparency on the part of the government and Barrick, and their refusal to provide even basic information to those suffering the brunt of the mine’s impacts.

The Pueblo Viejo mine is the sixth largest gold mine in the world and there has been mining activity at or near the site of the mine since the 1970s. The mine has had a number of different owners, and became a 60/40 joint venture between Canada-based Barrick Gold and U.S.-based Newmont in 2006. By purchasing the mine, Barrick became party to a special contract negotiated with the Dominican government which allows the company to lease about 40 square kilometers of land under or around the mining operations. Mining under the special contract is not subject to national mining law, and the contract included a clause that required Barrick to pay $37M in environmental remediation for contamination at the mine site, in return for being absolved of all future liability for historic contamination. Unfortunately, legacy and current environmental contamination continue to significantly impact downstream communities.

While in the Dominican Republic, we visited the area around the mine with the Comité Nuevo Renacer (CNR), an organization of six impacted communities advocating for relocation. It was striking to see the mine’s 114m tall tailings dam, called El Llagal, looming over the nearby communities when we visited houses that were less than half a kilometer from the dam. The El Llagal tailings dam has been classified as having an “Extreme” consequence of failure, meaning if the dam were to fail it would likely lead to over 100 lives lost, extremely high economic losses, and major environmental loss or deterioration where restoration or compensation in kind would be impossible.

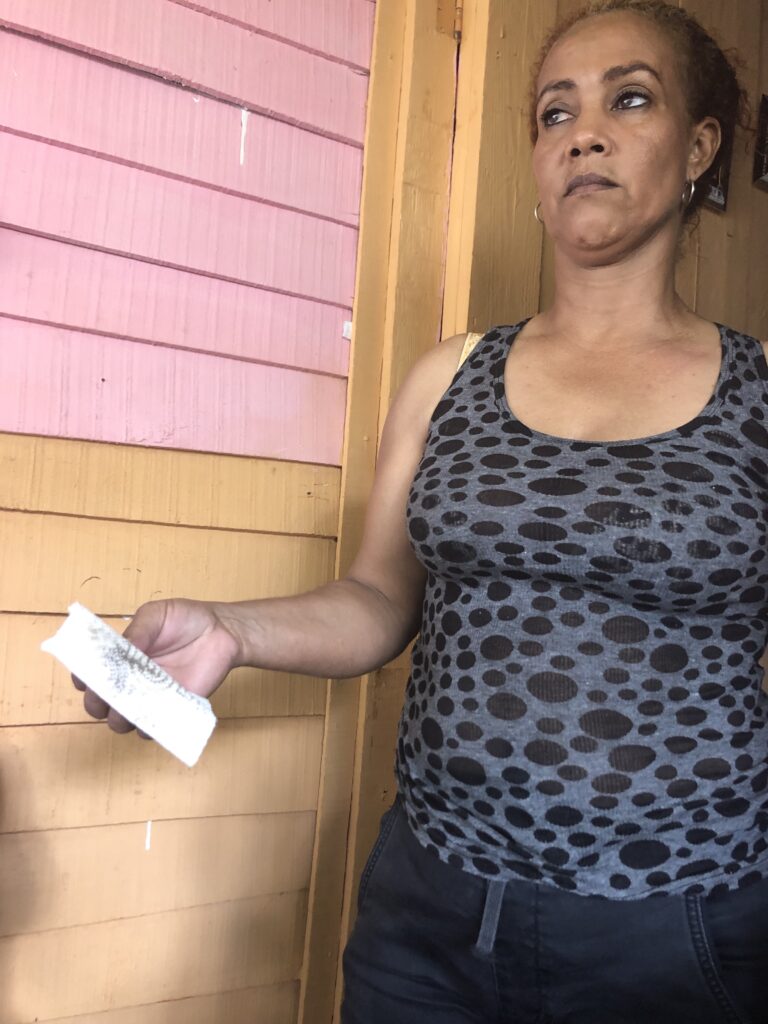

The communities downstream are feeling the effects of living in such close proximity to mine waste. Residents reported having to clean their houses daily to remove a layer of black dust that accumulates on every surface. Because of water contamination, communities have received bottled water for drinking and food preparation since 2011, first from the company, then from the government. Each family receives 15 gallons twice a week and often they have to rely on tap water for bathing and washing. Community members told us that local rivers have also been contaminated with heavy metals and toxins. There have been multiple reports of livestock deaths after drinking water from rivers below the tailings dam. Crops have also been affected and we were told that fruits like mangoes, plantains, oranges, and cacao grow but rot on the plant before they are ready to be harvested. This has created a food desert where communities are forced to travel to buy basic staples they once were able to produce themselves.

In 2014, a report by investigative journalist Nuria Piera published lab results showing cyanide and heavy metals in the blood of residents living in four communities near the mine. Health problems like vision loss, nausea, fatigue, and skin lesions are common in community members living near the mine. We spoke with residents who have been told they have elevated lead levels in their blood, and their doctors advised them that their health would not improve unless they moved away from the mining operations.

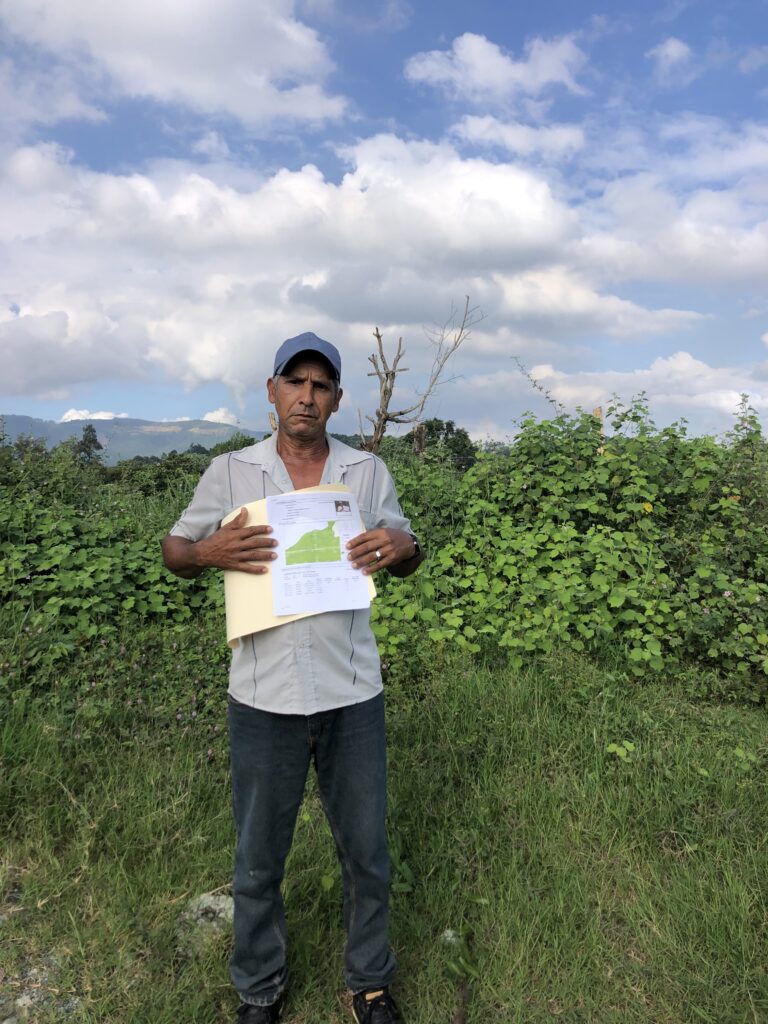

Barrick and Newmont built the El Llagal tailings dam in an area that displaced 65 households from three towns: El Llagal, Fátima and Los Cacaos. The Dominican government and members from the three communities negotiated a resettlement agreement. The agreement was signed in September of 2007 and the company reported paying $1.5M to support the process. While in the Dominican Republic, we visited the community of Nuevo Llagal where houses were built for the displaced families as part of the agreement. We heard that the relocation has been difficult because families were moved to a semi-urban area where they do not have access to land to plant food for their families and/or for their income. We heard from a number of women who said they have a hard time paying their bills. One resident of the town told us, “If I could go back in time, I would have stayed where I was.” We also spoke with farmers who lost the land that was their main source of income when the dam was built. They were promised land in return, but 13 years later still have not received any compensation or a comparable plot of land in a different location.

In spite of the fraught relocation process, six communities downstream from the tailings dam and next to the processing plant are demanding relocation as a result of the environmental and health problems associated with living next to the mine. At the insistence of the CNR and local residents, the Dominican government carried out a census that identified 369 families in the region that should qualify for relocation. However, to date, only the 65 original families have been able to complete the relocation process. The CNR has worked with partners like the Espacio Nacional por la Transparencia de la Industria Extractivas (ENTRE) to develop a community-centered relocation plan, but the government has not acted.

Now Barrick is looking to expand its operations, including tripling its land concessions via the special contract with the government and constructing a second tailings dam. The original location for the second dam was categorically rejected by the communities that would have been impacted by the project and the company was forced to look for a new site. The current proposal is to build the dam adjacent to the El Llagal dam which would displace five new communities. Communities and others have serious concerns about pushing ahead to build a new dam when significant environmental and human rights issues from current operations are still unresolved.