This blog was co-written by Earthworks International Mining Campaigner Jan Morrill and Mirko Nikolić of the Institute for Culture & Society at Linköping University.

In May of 2014 Serbia was hit by record rain: three months’ worth of rain, over 200 mm, fell in a single week. The extreme rainfall led to massive flooding and landslides across the country, taking 51 lives, forcing 32,000 people to evacuate and ultimately affecting 1.6 million people across 24 municipalities. The floods damaged or destroyed houses, roads, infrastructure, schools and hospitals, and impacted industries like agriculture, industrial plants and mines.

The Stolice Mine in Northwestern Serbia was hit particularly hard. The mine began operations in the early 1900s and mining in the region dates back to the previous century. Stolice was an antimony mine that reached its production height of 80,000 tons per year in the 1980s, but shut down in 1990 for financial reasons.

In 2006, the state-owned Stolice mine was part of a large wave of privatizations and sold to Farmakom MB, a Serbian junior mining company, part of a larger corporation that also produced car batteries, and dairy, pharmaceutical and agricultural products. The company rapidly accumulated 13 mines in Serbia and Macedonia and went on to develop a track record of dangerous labor, health & safety and environmental practices. Farmakom MB’s car battery recycling smelting operation in nearby Zajača caused health problems not only in workers but also elevated lead levels in 84% of children tested from surrounding communities.1 The company claimed at the time to be “a leader of the green economy in Serbia.”

In 2011, Farmakom M.B. received a large loan from the International Finance Corporation, which secured further investment from international and domestic banks. But by September of 2014, Farmakom MB had gone bankrupt and in November of the same year the owner of the company, Miroslav Bogićević, was arrested for bank fraud. Bogićević had been colluding with a lender from a state-run bank to receive 15 million Euros through fraudulent loan agreements. When the scandal broke, the Serbian Prime Minister announced that Bogićević, and others, had been offering up mine waste as collateral for those loans.

When the 2014 rains hit, the Stolice tailings dams contained an estimated 1.2 million tons of mine waste. The heavy rains triggered a landslide that damaged parts of the drainage system and rain accumulated inside one of the tailings dams, pushing it beyond capacity. A site review carried out by the Serbian water management agency, Srbijavode, showed the, “постојеће депоније јаловине немају одговарајући степен заштите. Депоније нису заштићене од спољних вода, које се неконтролисано сливају и испирају јаловину.” [existing tailings dumps do not have an adequate level of protection. They are not protected from external waters, which drain uncontrollably and wash away tailings]. One hundred thousand cubic meters of tailings were released into the Kostajnik River, creating a wave downstream that was 50 to 75 m wide and left everything in its path covered in a layer of toxic mud 5-10 cm thick. After another storm on July 17, tailings again spilled out of the damaged dam and into the Kostajnik.

After the spill, local residents were fearful of another disaster. One resident told local press, “Најгоре је живети у неизвесности. Нарочито је тешко кад падне мрак. Сваке ноћи сам будан, проверавам ниво реке, ослушкујем. Јер, ако брана попусти за минут-два јаловина стиже до нас” [The worst thing is to live in uncertainty. It is especially difficult when it gets dark. Every night I’m awake, checking the river level, listening. Because, if the dam drops, the tailings will reach us in a minute or two].”

Because the Kostajnik River is a tributary of the Jadar River, which flows into the Drina and Sava rivers, water pollution was widespread. A state report said flood damage, “је довела је до ослобађања опасних супстанци и отпада у животну средину, чиме је дошло до загађења површинских и подземних вода као и до загађења земљишта секундарним утицајима на екосистеме и на дивљи животињски свет (нпр. помор риба)” [led to the release of hazardous substances and waste into the environment, leading to pollution of surface and groundwater as well as to soil pollution, with secondary impacts on ecosystems and wildlife (e.g. fish death)]. The Serbian Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA) found elevated levels of arsenic, lead, copper and zinc in waterways as far away as the Sava River, over 100 km from the mine site. The government also reported 360 hectares of soil were affected by heavy metal contamination. The SEPA analysis of soil samples showed extremely high levels of arsenic, antimony, barium, zinc and lead. However, because of the lack of storage facilities for the contaminated soil, remediation work could not be done until the tailings dams were repaired and their stability was improved.

Unfortunately, the pace of repairs to the tailings dams and remediation efforts did not match the urgency outlined in the environmental studies. Newspapers reported that the initial repairs didn’t withstand the first rain storm and about a month after they were completed, the dam broke again. According to the local press, with every rainfall, tailings continued to wash into the local rivers, affecting 15,000 people downstream. It wasn’t until April 14, 2016, over two years after the initial dam break, that the Serbian government decided to use close to 2M euros from the EU’s Solidarity Fund to fully remediate the site. Construction and remediation efforts began in late June of 2016, but locals, “i dalje postavljaju jeste zašto je bilo potrebno čak dve godine da se zavrnu rukavi i krene u rešavanje jednog od najvećih ekoloških problema u Srbiji“ [still ask[ed] why it took two years to roll up their sleeves and start solving one of the biggest environmental problems in Serbia.

The dam failure at the Stolice mine and the mismanagement of the smelter waste in Zajača are examples of the dangerous nature of mine waste storage across the globe. Even though the Stolice mine was not operating, the tailings dams were a ticking time bomb waiting to go off. There is no comprehensive inventory of the thousands of closed and abandoned tailings dams worldwide, meaning there is no data on exactly how many there are and where they are located. Some estimates put active, closed and abandoned tailings facilities between 20,000 and 30,0000. Independent international oversight of tailings dams is necessary in order to identify closed and abandoned dams and assess their potential risk of failure.

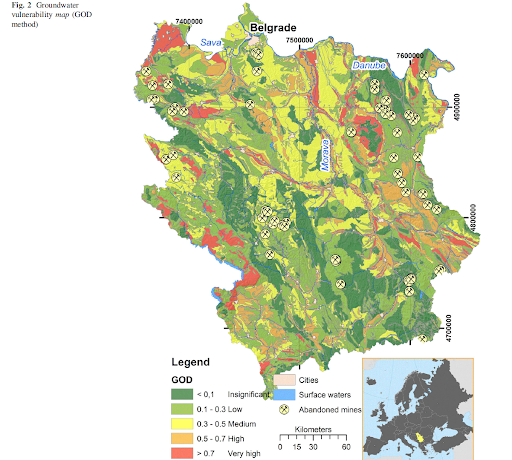

The Balkans have one of the longest mining histories in the world with a toxic heritage that is just beginning to be understood. For example, research shows continuous lead pollution dating back to 3,600 BCE in Western Serbia as a result of mining activities from the Bronze age through the 1800s. A recent water quality study of 59 abandoned mine sites in Serbia found “increases of sulfate and metal concentrations and general degradation of surface water quality,”and mapped the risks to groundwater vulnerability.

The Stolice dam failure shows how mining companies are unwilling and often unable to self-regulate to ensure the safety of their tailings dams. Farmakom MB inherited a dam that was susceptible to heavy rains and, as a junior mining company, didn’t have the financial resources, willingness or expertise to make necessary improvements. Its precarious financial situation and shady corporate leadership likely played a role in the eventual tailings dam disaster. And while the Stolice dam failure is certainly a case of negligence on the part of the mining company, it also highlights a network of other negligent actors, including the government, the domestic and international banks providing loans, and international institutions promoting privatization.

Extra attention and diligence are needed to regulate the mining industry. International standards and national regulations need to codify best practices in tailings management to address dangerous conditions for active and closed tailings dams instead of leaving it up to mining companies. Currently in Serbia and across the region, there are a number of closed mines and brownfield sites eyed for redevelopment, as well as mine take-overs, including by companies with problematic environmental and business records.2 These sites often come with legacy environmental issues, especially related to mine waste and acid mine drainage.

In 2020, 150 organizations, frontline communities and technical experts released a set of guidelines called Safety First that outline some best practices for tailings management. They include financial assurance and public liability insurance for tailings dams, which, had those been in force, could have prevented the cleanup costs at Stolice from being borne by the government and international funds. Mining companies should be required to provide funds up front for the risks associated with their tailings dams so local governments don’t get left holding the bill.

As severe weather events increase with climate change, mining operations become increasingly risky. The UN Climate Strategy & Action Plan Republic of Serbia Project Identification is predicting an, “increase in precipitation throughout majority of the territory in the 2011-2040 period.” These climate change predictions are concerning for new mining projects as well. The Anglo-Australian mining giant Rio Tinto is proposing a new lithium mine that would store tailings in the Štavica River valley. In addition, more than 5 million tonnes of mine waste will be stored in an industrial mine site adjacent to the Korenita River in the Jadar Valley. Local communities and environmental organizations are concerned that this new mine would have dangerous impacts on their water and agriculture, as well as two national parks and important cultural heritage and historic monuments in the area. This documentary explains the potentially dangerous effects of the mine and the community impacts. Learn more about the opposition to the mine here and follow the international support for the campaign here.

The authors would like to thank TV N1 for the use of the images in this article. TV N1’s coverage of the Stolice tailings dam failure is available here. We also extend thanks to Prof. Nebojša Atanacković for the use of the groundwater vulnerability map. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of N1 Serbia or Prof. Nebojša Atanacković.

- Farmakom’s operations in Zajača, a mere 5km from Kostajnik, faced both legacy pollution from historical antimony mine operations, as well as the company’s inadequate lead slag disposal and severe air pollution. Locals claim that with heavy rainfall, the waste seeped into the river Štira, flowing downstream to Loznica, and that the water supply was polluted and unfit for use. Dramatically increased lead levels were found in children’s blood, as well as grave health problems among the workers. Residents of Zajača raised the alarm about the environmental situation for years, and workers striked for unpaid wages. Finally, 600,000t of antimony and lead slag had to be remediated using c.1,8M Euros of public funds. The remediation plan was drafted by the government in 2012, however, because of delays and technical difficulties, the actual works didn’t begin until March 2016 and stretched until late 2018. In 2017, as part of bankruptcy proceedings, the smelter and the mine were acquired by a newly-formed company with no previous assets, and are slated to reopen. Activists, however, question the success of the previous remediation and claim contaminants still seep from the landfill. Neither Farmakom nor the authorities were held responsible for the terrible health toll on the local population.

- The most significant is the sale of the state-owned copper-gold mine RTB Bor to Zijin Mining in 2018. The area around the site has long suffered acid mine drainage issues and air pollution from the mine and smelter operations. Since the take-over, violations of air quality limits escalated, leading the municipal government to file charges against the company. The lead-zinc-gold mine Lece, owned by Farmakom (2008-2015) and now leased to Dubai-based Lifestone Capital, has reported several environmental incidents, as well as multiple accidents and deaths of mine workers. London-based ‘junior’ Mineco Group, scrutinised for their financial transactions, has acquired and “repaired” or “re-developed” four base metal mines between Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia since 2004.

Banner photo: Repairs made to retain tailings after the 2014 dam collapse. Credit: TV N1, Serbia