|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Is the automaker supply chain–a vast and intricate global network of manufacturers, suppliers, and service providers–getting cleaner to meet a just, safe, and responsible energy transition?

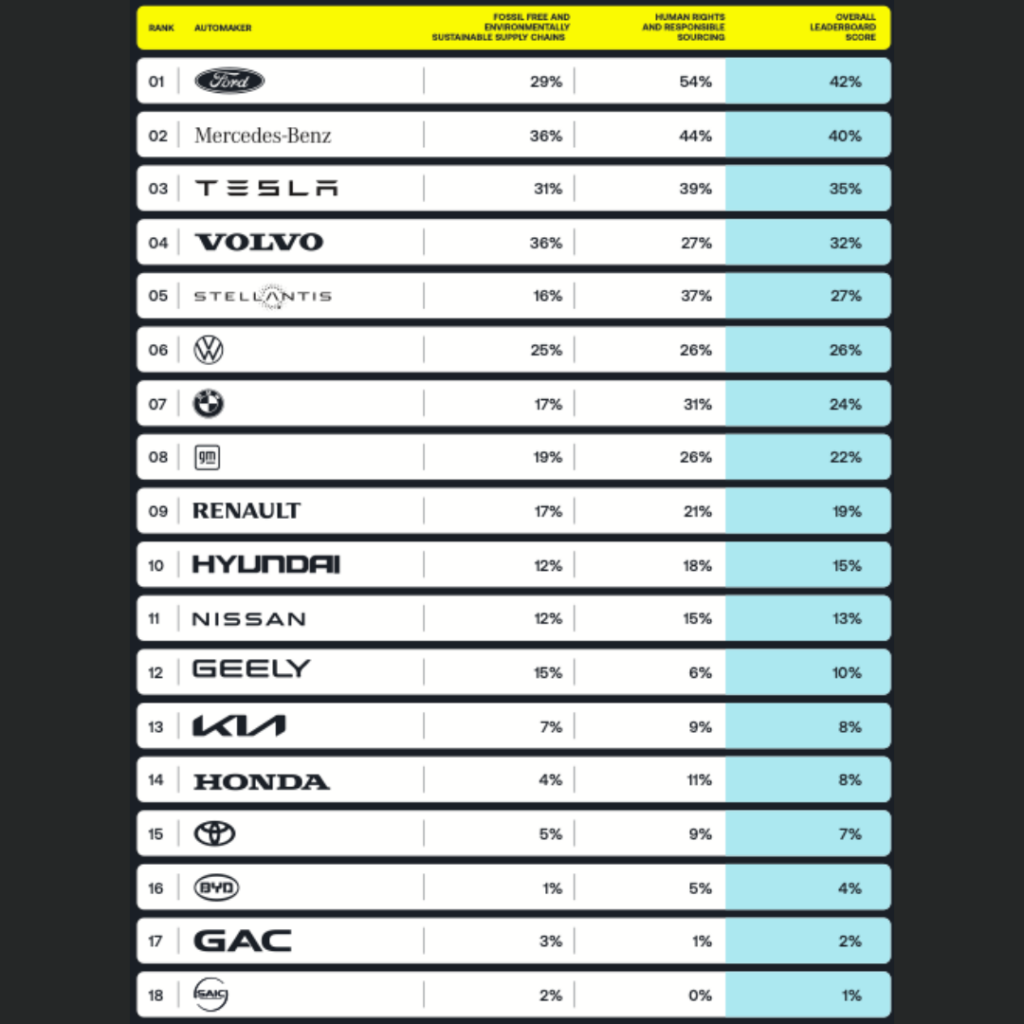

Lead the Charge (LtC), a coalition of human rights, environmental, and civil society organizations that includes Earthworks, has ranked the performance of 18 leading automakers in an independent report.

We found that some automaker companies, notably Ford and Tesla, have shown some progress on human rights and steel decarbonization. However, the industry still has a long way to go before it can meet its transition goals.

How did each fare in eliminating emissions and protecting human rights and the environment across their supply chains? Let us count the ways.

- The majority of the automakers failed to ensure their supply chains safeguarded the rights of Indigenous People.

Out of the 18 automakers, 11 did not assess Indigenous Rights risks in their supply chain. This is alarming because 54% of the world’s transition minerals are on or near Indigenous Peoples’ lands.

For change to happen, automakers must adhere to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent as enumerated in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Company policies must include in its due diligence the prevention and mitigation of harm and the establishment of formal mechanisms to remediate ongoing abuses and violations done to Indigenous communities and those impacted by mining.

Such terms must also be embedded in their contracts with suppliers, who must require the same from their manufacturers and source producers, especially mining companies.

- Third-party auditing schemes that certify auto supply chains are flawed.

Our 2023 Leaderboard report awarded automakers points for relying on accreditation and auditing schemes because it was an indicator of their commitment to responsible sourcing and other best practices.

This year, we went deeper by assessing their membership according to the rigor of these schemes. Why? Some are deeply flawed, causing civil society and communities to rightfully scrutinize the quality and credibility of eight schemes in certifying the human rights, environmental, and climate performance of mining sites, smelters, refiners, steel and aluminum plants, and other facilities.

Several did not have the elements necessary to protect people, communities, and the environment, such as multi-stakeholder governance, including rights holders during the audit process, and a time-bound corrective action plan to redress abuses and violations.

On February 6, Lead the Charge also released an assessment report detailing these deficiencies and recommended action points for automakers, investors, policymakers, and other stakeholders.

- Automakers’ reported performance on paper does not match actual implementation.

While 17 of the 18 automakers showed some improvements in their performance from last year, particularly from US companies, much still needs to be done.

One way forward is for governments to impose mandatory laws on automakers and companies, in general, to apply human rights and environmental due diligence across the supply chain. In doing so, companies must translate their green pledges into actions.

The European Union (EU) has been considering the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) to do just that. Worryingly, the vote to pass it was postponed because of concerns it would have fallen short of an unqualified majority. EU member states must support the adoption of the CSDD.

Hopefully, the US, China, and other countries will pass similar mandatory due diligence laws so companies, including automakers, can ensure that their global supply chains adhere to the highest standards of human rights and environmental laws, as well as protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and workers.

- EU legislation has inspired some positive developments from Chinese automakers.

While there is still uncertainty on whether the EU will pass the CSDDD, its application of the Battery Law and other similar laws have propelled Chinese automakers to improve their human rights indicators so they could do business in the EU market.

In a year’s time, Geely, BYD, and GAC moved from 0% on human rights and responsible sourcing to scoring a few points higher on several indicators under general human rights and transition minerals. While their performance is still poor, the movement shows that automakers can improve when pressured to do so. This highlights how much can be done if the 18 automakers implemented their peers’ best practices.

Know more about the Leaderboard report here.