This true story is filled with enough hubris, greed, unchecked power, a plague, and questionable relationships to fill a Greek tragedy. French energy giant TEP Barnett (Total) cannot drill in France where fracking is banned due to the harmful effects on health and the environment. So they came to Texas to drill where they want to frack in the middle of a minority neighborhood, next to a preschool that cares for black babies, during Black Lives Matter protests, while a pandemic is raging and in the very Arlington neighborhood with the highest number of COVID-19 cases. The Arlington City Council denied the permit with a 6-3 vote.

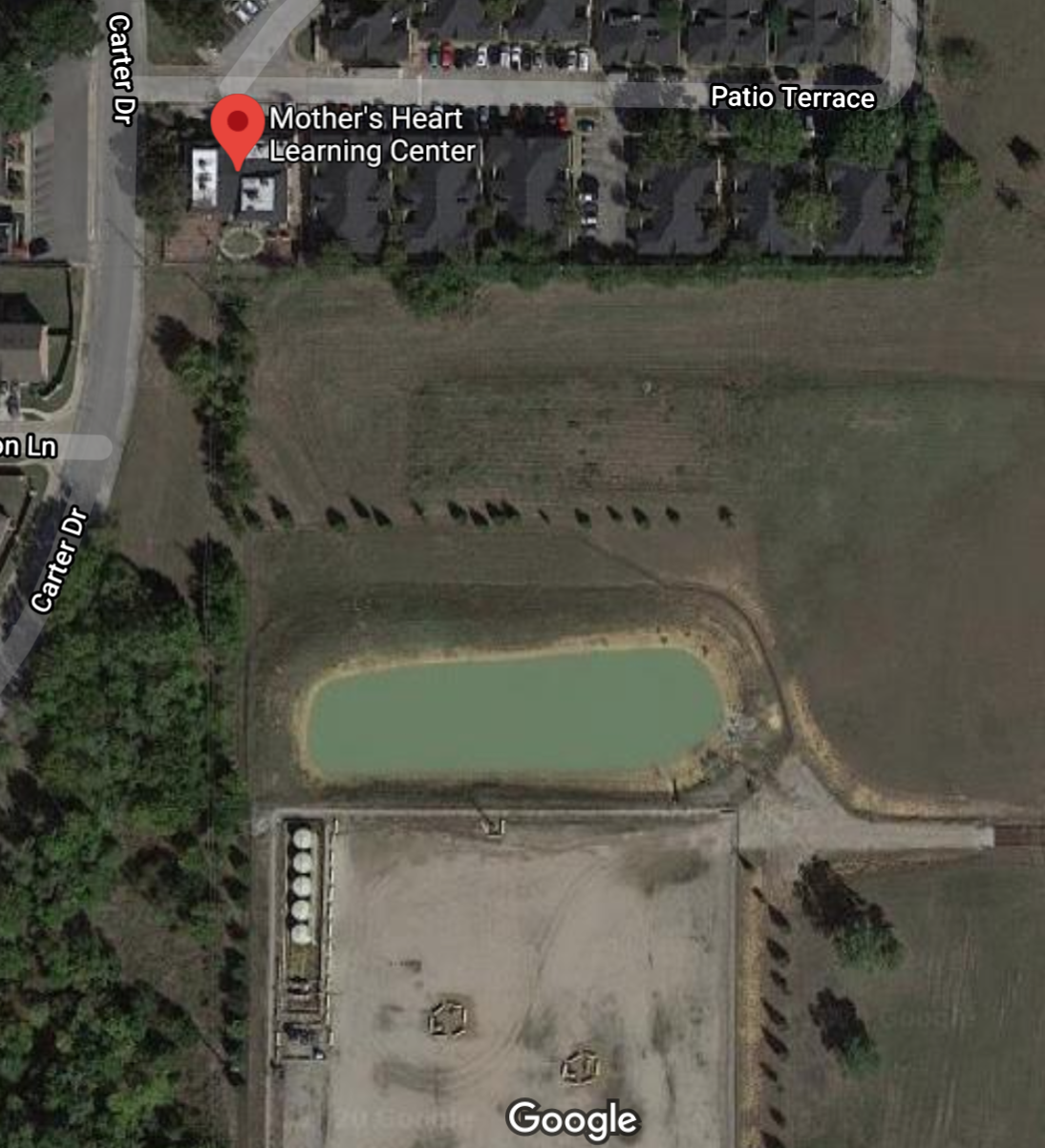

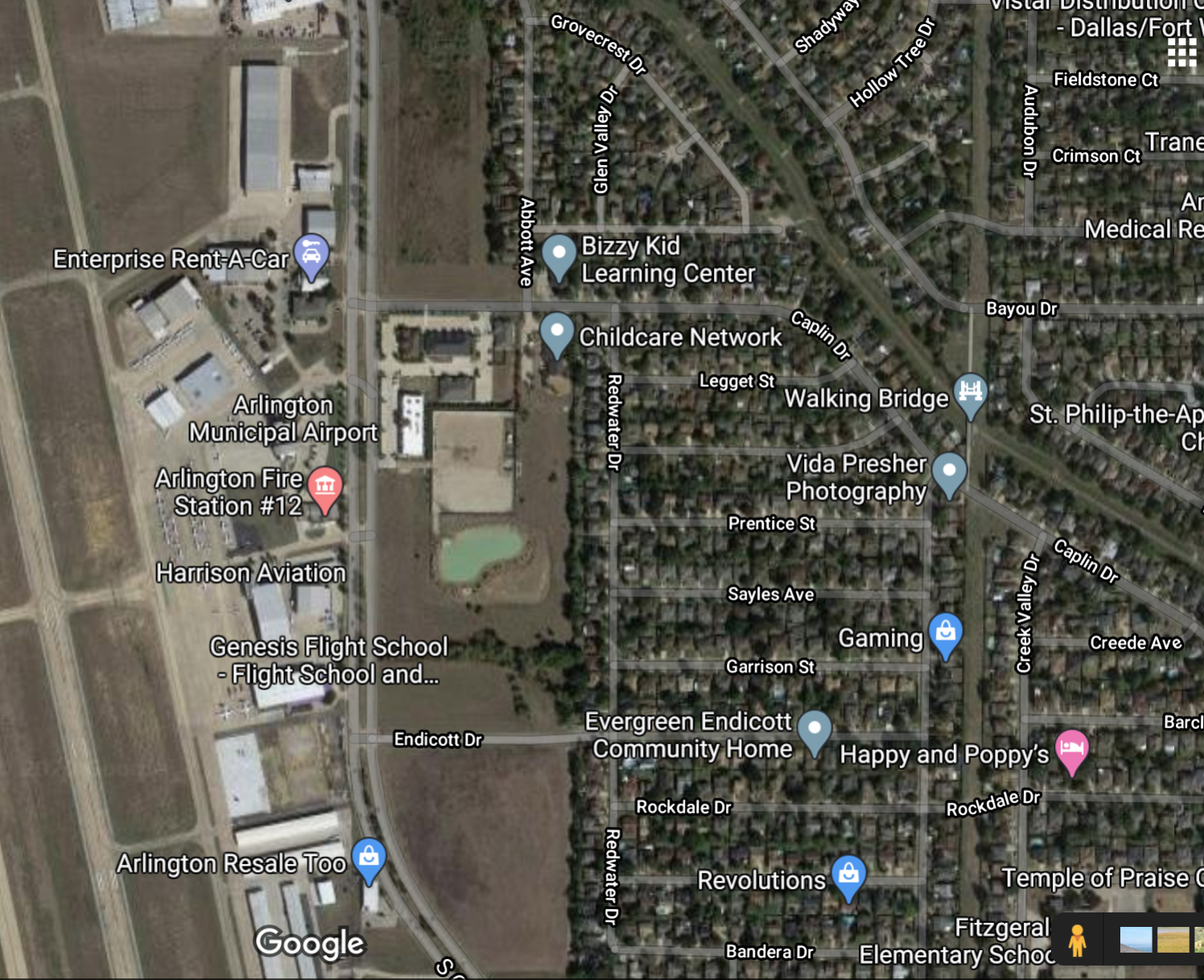

Now Total is coming back for more. We just learned that the Texas Railroad Commission granted Total permits to drill eight wells in Arlington. Seven of those wells are next to a childcare center and a preschool. Total has declared war on Arlington toddlers.

I testified against the Total wells near Mother’s Heart Learning Center, but I couldn’t say everything the city and residents needed to know during the 3-minutes allowed by the City of Arlington for testimony, so I’ll use this space for that.

The Greek Tragedy continues.

Total’s Drilling in Fort Worth

I received some calls from Fort Worth in January and February because Total was drilling additional new wells at an existing pad site right next to Top Golf and near a neighborhood in Fort Worth. I went there. Using an optical gas imaging (OGI) instrument that makes visible the normally invisible oil and gas pollution, I recorded a large plume of volatile organic compounds coming from the drill site. The hydrocarbon and chemical odors downwind were intense and caused dizziness.

Residents’ Odor Complaints Against Total

I waited until May to make a Public Information Request (PIR) to Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) for any complaints made and all the documents from any environmental investigations. I hoped this information would be useful to Arlington residents.

The surprising thing about the six complaints made while Total was drilling is that few people know where or how to make an odor complaint in Texas. It takes motivation to figure out who to call and to wade through the TCEQ complaint process. These complaints were made by residents of a neighborhood one mile away from the drill site.

-

- 328780 – January 23, 2020, 12:37 PM – bad air quality, bad odors when near the site. Same conditions occurring irregularly on other days when near the site. Odors can last for 2 – 4 hours.

- 328781 – January 22, 2020, 9:27 AM – a strong chemical cause coughing while driving near the regulated entity.

- 329106 – January 27, 2020, at 11:15 AM – gas like odor coming from the site is impacting

their property. - 329108-January 27, 2020, at 10:57- AM chemical/truck exhaust odor coming from

the site is impacting them. Impacted by odors in the morning’s similar odors occur regularly at other times of days and last 2 hours or more. - 329440 -February 3, 2020, at 9:11 AM – facility causing pollution and poor air quality.

Irregularly experience bad odors coming from site on other days lasting 3 hours or more. - 329764 – February 3, 2020, at 4:45 PM – solvent like odors

A TCEQ investigator, Ron Simpson, conducted field investigations on January 27th and again on February 5th when it was raining. OGI cannot be used during rain so why would TCEQ schedule and investigation during rain? Simpson noted visible emissions “steadily coming from the location next to the drill rig,” but the OGI video he recorded on February 5th is completely out of focus, unusable and does not meet quality standards set by the camera manufacturer and certification training. Where is the OGI video from January 27th noted in Simpson’s field notes?

Simpson’s field notes and his communication to Total were in agreement with the neighbors. He described the odors using: constant, pungent, and significant. Contrarily, odor descriptions in the final report given to complainants were described as “very light, intermittent.”

Drilling Mud

Simpson noted that Total was using oil-based drilling mud.

Oil-based drilling muds/fluids are not recommended for use when drilling in urban areas.WorkSafe, an organization that partners with workers and employers to create a safe workplace free of injury and illness, found that “More than 250 chemicals can be used to create drilling fluid. Some can cause serious illnesses, including cancer.”

They found that workers exposed to oil-based drilling fluids are at risk for:

- Dizziness

- Headaches

- Drowsiness

- Nausea

- Irritation and inflammation of the respiratory system

- Dermatitis

- Cancer

WorkSafe found that substituting a safer material and modifications to facilities such as keeping the muds/fluids enclosed were the most effective methods of control. Crestone Peak Resources routes hot drilling mud through a drilling mud chiller to cool the mud which “reduces the possibility that detectable odors will be produced near the well site.”

Several Texas municipalities have ordinances against oil-based muds/fluids:

Air Monitoring

Using a handheld MultiRAE Pro, Simpson recorded volatile organic compounds spiking to 2800 or 2900 parts per billion (ppb). He also used a Toxic Vapor Analyzer, but the report states he got no results which makes no sense because it’s a more sensitive instrument.

A 30-minute air sample was collected in a summa canister from 16:30 – 17:09, over two hours after the 14:25 arrival time. The sample should have been collected when Simpson arrived and initially noted the strong odors. Why the delay?

The canister sample had a broken chain-of-custody (C-O-C) on the Austin lab receipt side. There are three different C-O-C places for the Austin Laboratory side to sign to take possession of the sample, as it was relinquished at three different places by the investigator. The Austin lab did not mark the blank that states “custody seal was intact.”

The canister sample detected 53 of the 84 compounds TCEQ tests for including benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene, and xylene. Benzene, a known carcinogen, was detected as 1.3 ppb, just barely under the TCEQ long-term exposure limit of 1.4 ppb. A 1948 study commissioned by the American Petroleum Industry found that “the only absolutely safe concentration for benzene is zero.”

Total’s Response

Total’s response to the TCEQ Air Site Visit Questionnaire was incomplete, not forthcoming with required information, and needed followup from TCEQ. But we noted that the Total’s representative told the Arlington City Council that Total inspects each site once a month with an OGI instrument. Yet Total wrote on the Air Site Questionnaire that the Fort Worth site was previously inspected with OGI on February 20, 2019, almost a year ago.

The Regulatory Revolving Door

We used to watch as the regulatory revolving door turned. TCEQ and Texas Railroad Commission investigators are often lured by the high salary working for the ones they are supposed to regulate. For a while, I tried to keep track of the names. The revolving door is a huge problem and creates conflict of interest. An investigator who causes too much trouble for operators, might not get invited to the much higher salary on the other side of the door.

Rachel Jackson, Environmental Field Representative for Total, walked through the TCEQ regulatory revolving door in September 2017 and started working for Total that same month. From 2013 to 2017, she worked in the TCEQ Region 4 DFW office with Simpson, and her former coworker at TCEQ showed up to investigate the complaints against her current employer, Total. That might explain some things.

Pennsylvania Attorney General Shapiro blamed this revolving door in his condemnation of fracking and the failure of the Pennsylvania regulatory agency to regulate the oil and gas industry and protect people. Listen to the AG’s comments and you will see many similarities to the Texas regulatory agencies.

Protecting the Industry Against the Public

Unfortunately, TCEQ’s performance suggests that the Revolving Door might be better-termed Birds of a Feather. Through the years TCEQ has made clear that when it has to choose between protecting oil and gas operators or residents who are being harmed by those operators, it’ll pick the oil and gas company almost every time.

Whether it’s failing to follow its own transparency rules, or—upon finding pollution so bad that TCEQ evacuated its inspectors—it alerted (but did not sanction) the polluting company without informing the residents being poisoned, TCEQ has made clear that Arlington residents cannot rely on the state to protect them. The only way to protect themselves is not to allow fracking to occur anywhere nearby.

But until HB40 is repealed—which removed municipalities’ right to ban fracking within city boundaries—oil and gas corporations like Total can keep twisting the Arlington Council’s collective arm, and twist and twist and twist until they say yes.

Banner photo: Arlington City Council denied permits for French energy giant Total to drill wells near Mother’s Heart Learning Center, a preschool. Photo via Educational First Steps.