By a quarter-past-nine in the morning the Inter-American Development Bank’s (IDB) Andrés Bello Conference Room was already overflowing – dozens filled the space for a public seminar entitled The Lithium Triangle Initiative: South America’s Lithium Triangle and the Future of the Green Economy. The event was organized by the Wilson Center, the Argentina Project and the IDB.

We spent the next four hours listening to a series of pitches from Chilean and Argentine state representatives, alongside lithium mining and automotive executives. References to environmental and social impact were constant, but the depth, sincerity and transparency necessary to acknowledge these challenges in earnest was lacking, and the contradictions between a truly ‘green’ economy and the visions of the speakers were apparent.

For example, Martín Pérez de Solay, CEO of Orocobre, a lithium mining company operating in Argentina, proudly stated in his introduction that he spent more than a decade drilling oil wells up and down the continent “including in the Amazon”. An IDB Advisor on Citizen Engagement, Falvia Milano, also proudly referenced her role in helping garner a “social license” for oil and gas projects.

The claims made throughout the day to promote the region’s lithium extraction sector were often inconsistent with the concerns of locally-affected – largely indigenous – communities, alongside hydrologists, environmental scientists and several local and national NGOs. These diverse actors, none of whom were invited to participate, warn that this process is destabilizing hydrological systems – with potentially grave impacts on surrounding habitats, biodiversity, agricultural and pastoral livelihoods and freshwater access for communities.

Photo credit: Anders Beal

Making Clean Energy Clean, Just and Equitable

At Earthworks, we see the renewable energy transition as an opportunity to reduce our dependence on dirty mining. We urgently need to transition away from fossil fuels to mitigate the impacts of the ongoing climate breakdown. Yet the projected growth in renewable energy technology, particularly battery demand for private electric vehicles is justifying and garnering investment for irresponsible, dirty mining in geographic “hotspots”, particularly in the global south, and even in the deep sea.

Metal mining and refining is a dirty business with a long track record of environmental degradation and human rights abuses – disproportionately so for communities in the Global South and the indigenous North – it is also one of the principal drivers of the climate crisis, responsible for 10% of global carbon emissions.

In order to ensure that our clean energy economy is truly clean, just and equitable, we must develop a shared commitment to responsible mineral sourcing which prioritizes the right to consent and self-determination of affected people, alongside a massive increase in the reuse and recycling of metals, and the reduction and redistribution of global energy and mineral demand.

Lithium extraction from brine

Evaporitic lithium extraction from salt flats involves the pumping of brine, a highly salinated mineral-rich fossil water (water that has been accumulating for millenia under the salt flat) onto the salt flat’s surface where it is decanted from one artificial pool to another as solar radiation and wind evaporate away the brine’s water content, leaving behind progressively greater concentrations of salts. In total, this method to increase the concentration of lithium chloride from its natural occurence to a commercial grade takes roughly 18 months.

This brine contains a host of minerals: potassium, boron, magnesium, sodium and lithium chlorides are all found in this unique water. The Lickanantay people of the Atacama consider the brine to be a sacred and inextricable part of their territory. In stark contrast, the mining executives in the room referred to the brine as unfit for consumption and thus of no social or ecological value. This ancient, fossil water also sustains the life of microorganisms whose role in the broader ecosystem is still not fully understood.

Freshwater impacts

Beyond the brine itself, the interconnected aquifers around the salt flat contain freshwater bodies and a brackish interstitial space where these bodies meet and mix. The hydrology of each salt flat and salt lake is unique, however the concern that the pumping of brine may impact the surrounding freshwater aquifers is widespread throughout the region. The issue remains insufficiently studied – an uncertainty acknowledged by Chile’s Environmental Tribunal in their decision to reject the expansion plans of SQM (Chile’s largest lithium producer), if not by its investment and mining agencies present at the IDB.

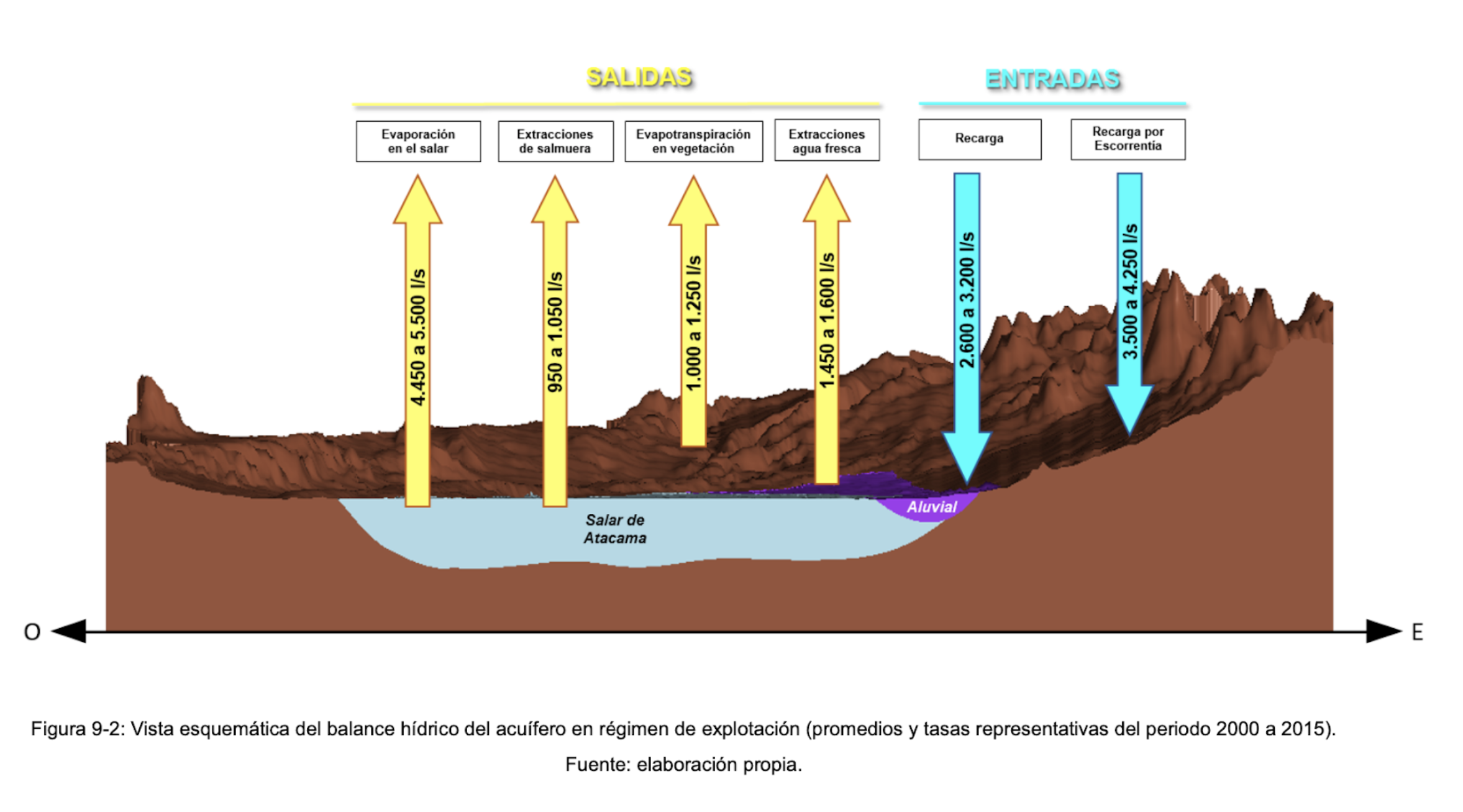

But ultimately, the math is simple – to take the example of perhaps the most well-studied salt flat, the Atacama – the water table is losing an estimated 1,750-1,950 liters per second more than what enters from rain, filtration and run-off water. This is largely due to the extraction of water from two massive open-pit copper mining projects: BHP’s Escondida and Antofagasta Minerals’ Zaldivar, and brine from two sizeable lithium operations: those of SQM and Albemarle.

Source: Estudio de modelos hidrogeológicos conceptuales integrados, para los salares de Atacama, Maricunga y Pedernales, Informe Final, Modelo Hidrogeológico Consolidado Cuenca Salar de Atacama, (Comité de Minería No Metálica CORFO), 30 de agosto 2018, p. 352.

Frontline voices

The stark gap between the concerns of those affected and the narrative of mining companies and the state representatives whose responsibility it is to regulate and oversee their activities, highlights the need to elevate the voices of communities, independent researchers and NGOs speaking out about the unprecedented wave of investment and encroaching corporate interests in this region which is home to Kolla, Atacameño, Lickanantay and Aymara communities – communities who have persisted in the face of centuries of (neo)colonialism. With a wide range of tactics, from court cases to roadblocks, people across the region have been demonstrating their opposition and fighting to defend their livelihoods and these wetland oases that harbor unique forms of life in the midst of some of the world’s driest deserts.

Making Clean Energy Clean, Just and Equitable aims to help bridge this gap by ensuring that the clamor for metals does not trample on the rights of communities to self-determination, nor the survival of ecosystems like the Andean salt flats of Chile, Argentina and Bolivia.

For more information

Reports and media in English:

- Report: Responsible Minerals Sourcing for Renewable Energy (UTS-ISF for Earthworks)

- Report: Lithium extraction in Argentina: a case study on the social and environmental impacts (FARN)

- Short video: Will green technology kill Chile’s deserts? (Guardian)

- Article: Lithium extraction for e-mobility robs Chilean communities of water (DW)

Informes y medios en español:

- Revista: Pulso Ambiental #10 – Litio (FARN)

- Blog: Observatorio Plurinacional de Salares Andinos (OPSAL)

- Artículo de prensa: Explotación de litio deja sin agua a pobladores (DW)