By Sayyidatiihayaa Afra, Researcher of Satya Bumi.

When Indonesian President Joko Widodo visited the White House in November 2023, he had one thing on his mind: selling President Biden on a trade agreement that would facilitate the flow of Indonesian nickel to the United States. It’s an appealing prospect. Biden has made bold promises to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels, and Indonesia has the world’s largest reserves of nickel, one of the key metals used in the production of electric vehicle batteries. But we and other Indonesian civil society organizations have deep concerns, which we shared in a letter with President Biden.

In the end, President Widodo went home empty-handed. As of this writing, any such trade deal faces long odds for a simple reason: longstanding trade tensions between the United States and China. Chinese companies dominate the Indonesian nickel mining and processing industries, and would be the primary beneficiaries of any deal. Yet the problems entrenched in Indonesian nickel cannot be reduced to China-U.S. trade problems.

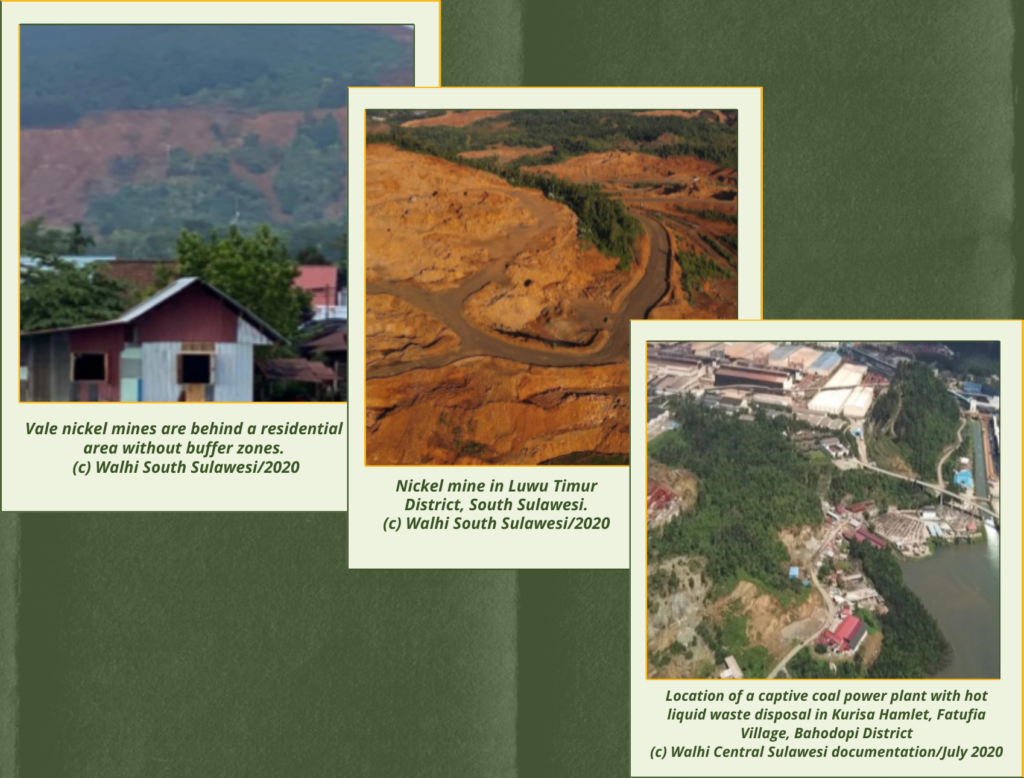

Since 2000, when nickel became a mining commodity in Indonesia, extraction has caused massive environmental damage. Indonesian nickel mining has led to deforestation in biodiversity hotspots, displacement of uncontacted tribes such as the Hongana Manyawa and contamination of sensitive reef habitat in the Coral Triangle. In October, nine U.S. Senators submitted an open letter opposing a trade deal citing these and other concerns, including weak labor protection and the lack of meaningful consultation with impacted communities.

President Widodo is aware of these concerns, and has encouraged the Indonesian mining sector to comply with international standards, such as the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance. This is a good sign. Unfortunately, the Widodo government is also actively undermining Indonesia’s existing environmental safeguards. For instance, the administration weakened environmental protection through the Mining Law and Job Creation Law, which reduces the involvement of civil society in preparing environmental impact studies.

Meanwhile, updates to the Mining Law allow companies to automatically extend concessions for up to 20 years. Indonesian lawmakers also recently withdrew the authority of regional governments to supervise mining implementation and relaxed reclamation obligations. Mining companies are allowed to dispose of their waste in the sea and dig for nickel in protected forests. The People Representative and Corruption Eradication Commission, which is supposed to offer some oversight, has been weakened through various legal instruments and rendered effectively powerless.

As an example of the absence of good mining governance, Satya Bumi, together with WALHI South Sulawesi, Walhi Southeast Sulawesi, and Walhi Central Sulawesi, found that 330 nickel concessions in Indonesia are destroying core biodiversity areas. In Sulawesi alone, at least 51 thousand hectares of core biodiversity areas have been destroyed by nickel mining. On a national level, from 2000 to 2023, a total of 156,281 hectares of forest have been impacted by nickel mines. A de facto ban by the Indonesian government on the practice of submarine tailings disposal hasn’t stopped waste from mineral processing at the Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park from contaminating fish and other sea life. The waters of the Morowali Sea have 76% of the world’s coral reefs, 37% of coral reef fish, and the world’s largest mangrove forest—a critical source of carbon sequestration.

The government also uses the military to protect resources and developments that it considers of strategic value, including nickel mines and processing facilities. This can even involve using force against local people who oppose these projects. As a result, clashes between the police, soldiers, and residents in mining areas have become a regular occurrence.

While demand continues to grow for green energy sourced from a clean supply chain, Indonesia is still stuck on the idea of green energy through dirty nickel mining practices. Until the nickel supply chain is improved, advertising responsible Indonesian nickel on the global market is nothing but greenwashing. It is high time for the Indonesian government to address these issues and work towards establishing a clean, fair, and sustainable supply chain for nickel.